BEYOND THE NUMBERS

House Bills Expanding HSAs Would Boost High-Income Tax Breaks — Not Affordability of Care

Two bills due for House Ways and Means Committee consideration this week contain a slate of provisions that would expand health savings accounts (HSAs) — increasing tax breaks that overwhelmingly benefit high-income people, exacerbating racial and ethnic differences in wealth, and costing over $70 billion combined, without tackling the most urgent problems people with low incomes face in accessing affordable health care.

Under current law, people enrolled in high-deductible health plans that meet certain standards can establish and set aside money in an HSA. These accounts offer a unique “triple tax advantage” enjoyed mostly by high-income people: (1) contributions are not taxed; (2) contributions can be invested for years in stocks and bonds with tax-free earnings; and (3) withdrawals are not taxable if they are used for qualified medical expenses that occurred after establishment of the HSA.

People with low and moderate incomes are far less likely to be able to contribute substantial savings to their HSAs compared to high-income people. And people with low and moderate incomes benefit much less for each dollar contributed, because they are in lower marginal income tax brackets. For example, a married couple earning $80,000 per year can deduct 12 cents for each dollar contributed to an HSA from their taxes, while a married couple earning $700,000 per year can deduct 37 cents for each dollar put into an HSA.

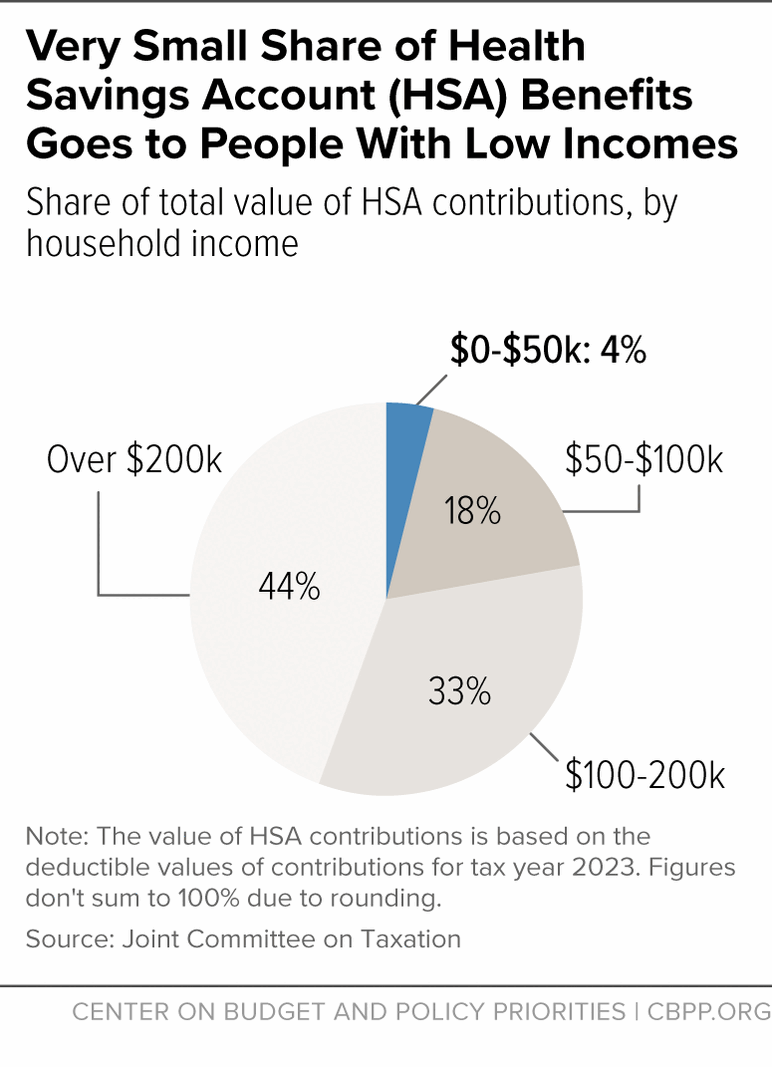

Data show that the benefits of HSAs skew heavily toward people with high incomes. An analysis of 2017 IRS data found that tax returns exceeding $500,000 in adjusted gross income were the most likely to report individual HSA contributions, and returns between $200,000 and $1 million were the most likely to report employer contributions. According to Joint Committee on Taxation estimates for tax year 2023, 77 percent of the total deductible value of HSA contributions goes to households with incomes over $100,000. (See graph.) Only 4 percent of the value goes to households with incomes $50,000 or below, and 44 percent goes to those with incomes over $200,000.

The House bills would expand HSA tax benefits, primarily helping high-income people, in various ways: by allowing more types of health plans to qualify for use with them, increasing how much people can contribute to their accounts, and allowing new health services to be covered pre-deductible without running afoul of federal tax rules.

For example, one provision would allow health plans that cover $500 of mental health services pre-deductible to qualify for HSA tax breaks. Another would let people who get care from a worksite clinic to get HSA tax benefits. Other provisions would newly allow Medicare enrollees to contribute to an HSA, allow people 55 and older to put more money in their accounts, and deem “bronze” and catastrophic plans under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as qualifying for HSA tax breaks.

While making health care more affordable is a critical priority, and some of the provisions are directed at populations or health care services in need of support, they do not target help to the people who need it most ― especially those with low and moderate incomes who are struggling to access health coverage and care.

Also making these bills counterproductive is their promotion of racial wealth differences. Privately insured Latino and Black people are about half as likely to have HSAs than are white and Asian people. This, combined with the accounts’ use as lucrative tax shelters, represents one of the many ways in which access to economic opportunity is inequitable, and it exacerbates long-standing differences in wealth, under which a typical white family in 2019 had eight times the wealth of a typical Black family and five times the wealth of a typical Latino family.

HSA tax breaks also come at a steep cost; they are already projected to cost the federal government $180 billion over the next ten years. The new provisions, which are assumed to be in effect after 2025, are estimated to cost over $70 billion combined over the eight years from 2026 through 2033, with costs increasing each year. Instead of throwing more money into these tax breaks, policymakers should target federal resources toward expanding coverage, increasing affordability, and improving health equity.

For example, for states that haven’t adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion, the federal government should close the Medicaid coverage gap, which would focus resources squarely on helping uninsured people below the poverty line — 60 percent of whom are people of color. Policymakers should also permanently extend enhanced premium tax credits for ACA marketplace plans, which are set to expire after 2025. These tax credits, unlike HSAs, have made health insurance more affordable for millions of people, narrowed racial differences in coverage rates, and helped fuel record coverage gains.