Update: This paper has been revised to reflect new inflation data released on February 24.

After the major economic disruption caused by an unprecedented global pandemic, the economy has healed considerably. Economic developments in the second half of 2022 were encouraging and should give pause to Federal Reserve officials as they consider the next steps for achieving their twin goals of price stability and high employment.

Namely, inflation and wage growth came down significantly in the second half of the year, and job growth, while still strong, cooled over that period as well. Inflation expectations — what the public and financial markets believe will happen to inflation over the next couple of years — indicate that people (and financial markets) believe inflation will continue to fall, which is key to reducing upward pressure on nominal wages that could trigger more inflation.[1]

Data for January have been more difficult to interpret, with very strong job growth reported, but much of that growth is likely due to idiosyncratic measurement issues rather than an acceleration in the job growth trend. Similarly, the inflation data are confusing for January: the consumer price index (CPI) is up 3.5 percent at an annual rate over the last three months, but the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) price index is up 4 percent over the same period.[2]

To be sure, the U.S. is not out of the woods on inflation yet — we don’t know if the slowing since mid-2022 will continue toward a stable rate consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target, low unemployment, and solid real (inflation-adjusted) wage growth. Month-over-month inflation can be volatile, but the overall positive trends should mean that the Fed has some breathing room to assess the economy’s trajectory before deciding whether to continue raising interest rates.

One important consideration for the Fed should be the downsides to raising rates too high and triggering a recession. Even a modest recession will lead to rising unemployment and a significant increase in the number of households facing real hardship.

If the economy goes into recession, the Fed could reverse course and lower interest rates, but monetary policy affects the economy with a lag, which means that hardship will remain high for some time. Moreover, monetary policy alone will not target help to those who need it and may be inadequate for the job of helping the economy rebound quickly. But in today’s political environment, it likely would be very difficult — perhaps impossible — to quickly enact stimulative fiscal policy measures like emergency unemployment insurance to support demand for goods and services and relieve hardship for unemployed workers, their families, and others hurt by a recession.

While going too far or too fast with rate hikes can have serious consequences, some observers have raised whether going too slowly could also have downsides, particularly since many think the Fed should have acted sooner to raise rates as inflation rose in 2021. Given how much inflation has moderated and that the public and financial markets expect lower inflation in the future, a modest pause to evaluate additional months of economic data while maintaining a strong commitment to future interest rate hikes if they are necessary should carry smaller risks than the recession risks from raising rates too much.

At its January meeting, the Fed raised its target interest rate by 0.25 percentage point, but unlike Canada’s central bank, which suggested it may take a pause, the Fed indicated that it is not done raising rates. Most observers think a 0.25 percentage point increase at each of the next two Fed meetings in late March and May is very likely (and some are calling for a larger increase after the January PCE report). Given the uncertainty surrounding recent economic data and the serious downsides to a recession, caution and patience on the part of the Fed are warranted. The Fed can and should communicate that pauses to assess the balance of risks need not compromise its commitment to making steady progress toward its inflation goal.

Let’s look at the data and the decisions facing the Fed.

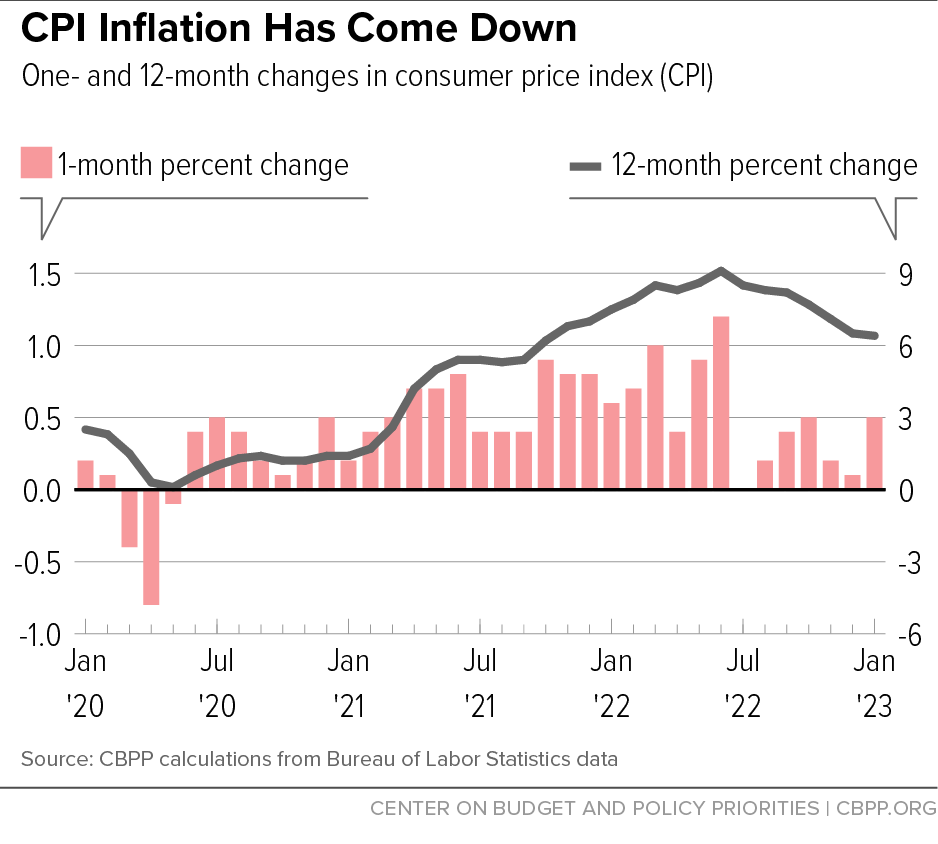

Both inflation and economists’ evaluations of inflation have been on a roller coaster for the past three years. The sharp contraction in economic activity in the March-April 2020 recession was accompanied by a sharp decline in inflation. (The line in Figure 1 shows the most widely followed measure, the percentage change from a year earlier in the consumer price index or CPI, on the left scale, and the bars show the monthly percentage change on the right scale.) CPI inflation, while rising, remained below 2 percent early in 2021, as it had been for several years before the pandemic. But inflation shot up in the spring.

The Federal Reserve and many economists viewed the rise in inflation in early 2021 as a “transitory” increase in prices largely associated with the global economy’s difficulty supplying goods and services to meet rising demand as the economy continued its recovery from the pandemic recession.[3] Pandemic-driven supply bottlenecks and shortages of materials in some sectors led to very large price spikes and windfall profits in those sectors. In a rapidly reopening economy, many employers faced labor shortages that put upward pressure on wages. These inflationary pressures were expected to resolve relatively quickly.

But inflation proved to be more persistent than expected, with 12-month CPI inflation peaking at 9.1 percent in June 2022, as the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 affected food and energy prices worldwide as well as near-term inflation expectations.

Long-term inflation expectations, however, remained largely unaffected.

Since the June 2022 high point, however, CPI inflation has been coming down, as evident in the much lower month-over-month inflation in the second half of 2022, compared with the first half. Near-term changes in the CPI have generally been much smaller in recent months, with the three-month change expressed at an annual rate falling to 3.3 percent in December before edging up to 3.5 percent in January.

Analysts often focus on inflation in the CPI excluding food and energy, which has also slowed, although not as much as the overall CPI. This “core” inflation measure rose at a 4.3 percent annual rate in the last three months of 2022, compared with 6.4 percent over the three months ending in July.[4] Although measured inflation is still greater than the Fed’s target, inflation expectations continue to reflect public and financial market confidence that inflation will return to that target.

As month-over-month inflation fell, the “headline” annual rate also fell, but more slowly because the annual rate compares prices in a month to those 12 months earlier. The 12-month rate fell to 6.5 percent in December and 6.4 percent in January.

The way the CPI measures shelter costs also complicates the analysis of inflation trends. Shelter services (measured either as actual rent or “owners’ equivalent rent” for homeowners) are a major component of the CPI, accounting for about a third of the goods and services in the index. It takes time, however, for changes in shelter costs to be reflected in the CPI, as rent typically only changes once a year for people with annual leases. Housing inflation has now slowed considerably for people entering into new leases, but the lag means that it will take time before the changed trajectory in housing inflation shows up as creating downward pressure on the CPI overall and the CPI for services in particular.[5]

While the CPI is the most recognized measure of inflation, the Federal Reserve focuses on the PCE index. Revisions to those data released in February show less progress against inflation than data available in January showed. These may reflect technical issues, but they could nevertheless lead the Fed to be more aggressive with rate increases that increase recession risks.

Job Market Remains Healthy

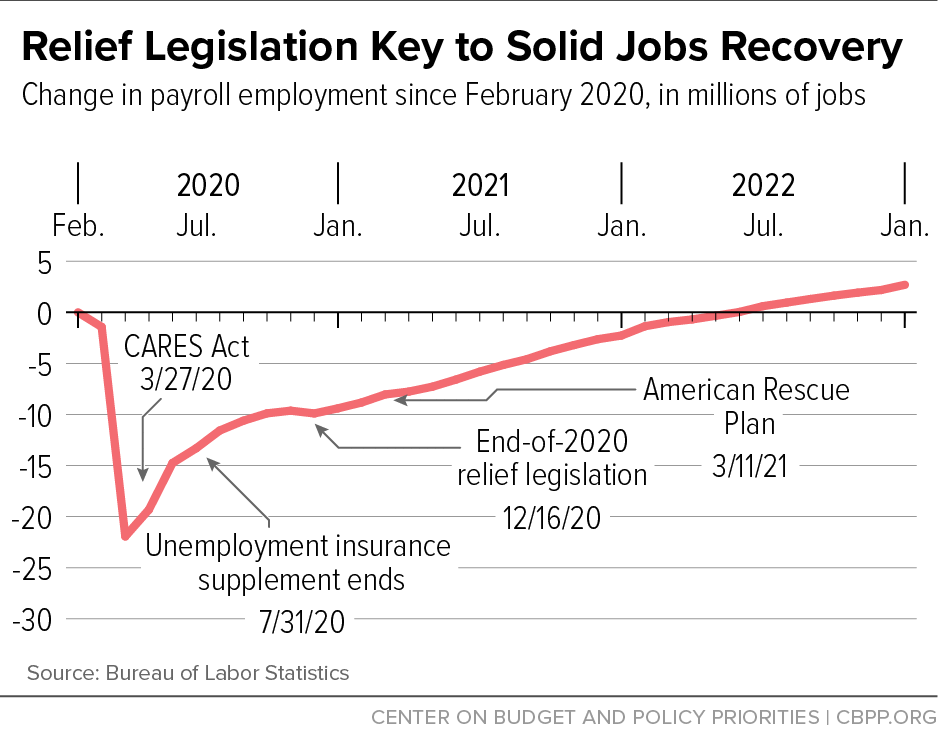

Total nonfarm employment fell by 1.5 million jobs in March 2020 and a staggering 20.5 million jobs in April, creating a jobs deficit of 22 million compared with February 2020 and largely erasing the gains from the previous decade of job growth. A strong policy response in early 2020, however, helped reverse some of the initial job losses, and progress against the pandemic as well as subsequent policy steps taken at the end of 2020 and in early 2021 helped re-energize a jobs recovery that has since erased April 2020’s huge jobs deficit. (See Figure 2.)

Since the trough of the recession in May 2020, every month except December 2020 has seen job gains. In December 2022, payroll employment was 2.2 million jobs above its February 2020 level and very close to the projected level for the fourth quarter of 2022 in the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) last pre-pandemic forecast in January 2020.

Job growth in 2022 averaged 401,000 jobs a month, down from 606,000 per month in 2021 but still quite strong. Job growth slowed to a still solid 291,000 jobs per month in the fourth quarter of 2022 (October-December), indicating that the job market is gradually returning to more normal levels of job growth as the economy heals from the upheaval of an unprecedented recession.[6]

The unemployment rate in December 2022 was 3.5 percent. This is the same as it was at the peak of the previous expansion in February 2020, which was the lowest it has been in over 50 years. The unemployment rate fell below 4 percent in July 2018 and remained below 4 percent in every month except January 2019 until the pandemic hit and unemployment spiked in early 2020. As discussed more below, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and white unemployment rates all fell to historically low levels in that period. During that period of low unemployment, inflation remained very low — with the average annual rate of CPI inflation just 1.9 percent from July 2018 to February 2020.

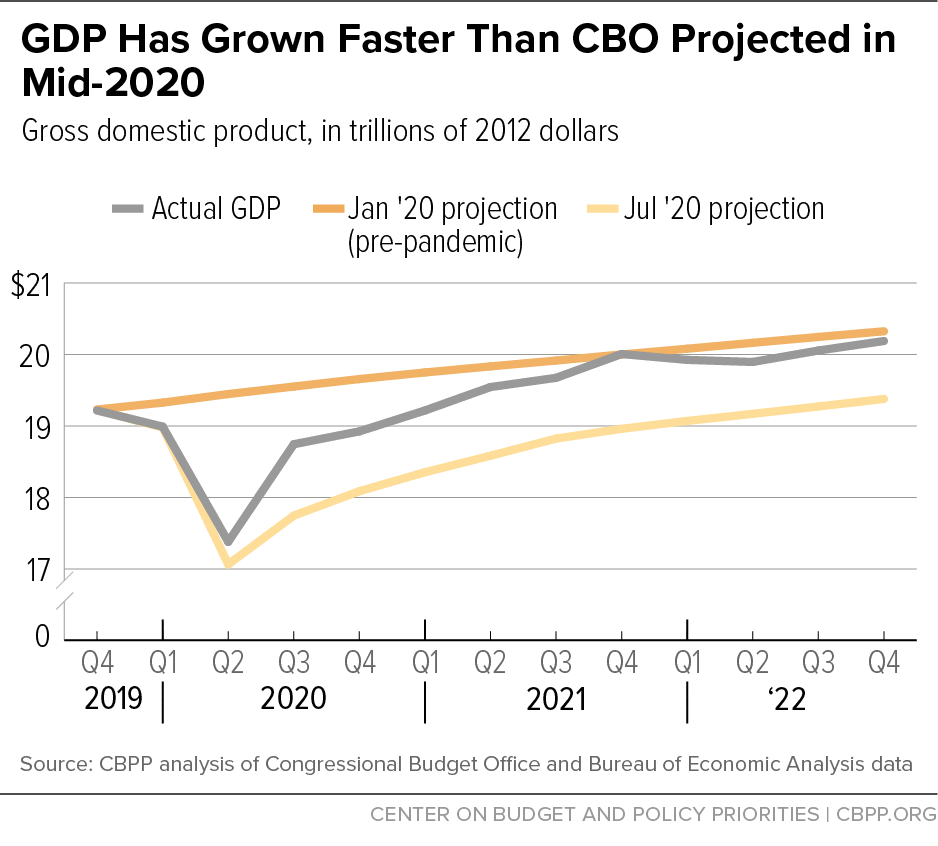

The relief and recovery measures that spurred the jobs revival also spurred strong economic growth coming out of the pandemic recession. Real gross domestic product (GDP) surpassed its pre-recession peak in the second quarter of 2021, just one year after the trough of the recession. This recovery was much more robust than the CBO’s mid-2020 projections for GDP growth. (See Figure 3.)

Growth faltered in the first half of 2022, with negative growth in the first two quarters of the year raising concerns in some quarters that the economy could already be in a recession. Growth in the third and fourth quarters erased those losses, and GDP in the fourth quarter was 0.9 percent higher than a year earlier. Of some concern, however, is a weakening of consumer spending, the largest component of GDP, in preliminary data for the fourth quarter,[7] which could be a warning sign that the economy could cool further.

The job market remains strong and unemployment remains low, as described above. But nominal wage growth over the 12 months ending in December was both higher than is consistent with meeting the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation target and lower than would have been necessary to achieve real wage gains over that period.

The Federal Reserve and many economists continue to express a concern that the labor market is too tight and that will keep wage growth and inflation high. Their logic is the following:

Broadly speaking and over time, the inflation-adjusted wages and benefits businesses can pay while maintaining a constant profit margin can grow at the rate of growth of labor productivity (output per hour), which was about 1.5 percent per year in the nonfarm business sector in the three years just before the pandemic. If prices are rising at a 2 percent annual rate consistent with the Fed’s inflation target, employers can raise nominal wages at a 3.5 percent annual rate while maintaining normal profit margins. Real wages, on average, would then rise at a 1.5 percent annual rate, consistent with productivity growth.

But wages don’t necessarily have to bear the full burden of adjustment to reach 2 percent inflation. Corporate profit margins are larger than normal historically,[8] so part of the adjustment should come through an adjustment of profit margins down to more normal levels. Some of the adjustment could also come through an increase in labor’s share of business income, which was above 60 percent from 1947 through 2004 but has averaged 57 percent since. Lower profit margins and a larger labor share can happen in a tight labor market that increases workers’ wage-bargaining power. Faster labor productivity growth could also boost real wages.

The employment cost index (ECI) is perhaps the best regularly published measure of growth in wages, salaries, and benefits. The ECI is released quarterly. Unlike the monthly jobs report’s average annual earnings data, the ECI is a measure that holds the mix of jobs constant for a better read on changes in average hourly earnings over time.[9] Both wages and salaries and compensation (wages and salaries plus benefits) rose 5.1 percent over the course of 2022 for civilian workers. In the last three months of 2022, compensation costs moderated, rising 1 percent (4 percent at an annual rate). Both compensation and wages and salaries grew more slowly than inflation from December 2021 to December 2022, but each grew somewhat faster than inflation in the second half of the year, which means that workers were starting to experience real wage gains again. Some economists look at wages and salaries for all occupations less incentive-paid occupations (where pay is not related to hours worked). This measure grew 5 percent over the course of 2022, but only 3.2 percent at an annual rate in the last three months.

The ECI data show that wage growth is moderating but may not yet be as low as is needed to be consistent with the Fed’s inflation target. However, the trajectory is in the right direction, giving the Fed breathing room to assess further data.

Concern that labor markets are too tight also rests on estimates from the Job Openings and Labor Market Turnover Survey that showed a surge in job openings and quits to unprecedented levels relative to the supply of workers in 2021, which only eased modestly in the second half of 2022. If taken literally, those estimates imply a shortage of workers, which would put upward pressure on nominal wages and inflation if those labor costs get passed through into prices. But there is uncertainty about how serious employers are about filling all their openings. If employers were not working very hard to fill most openings or had no plans to fill some of them in the near term, the number of actual openings to be filled could be significantly overstated. There is also uncertainty about the accuracy of the survey data because the share of employers responding to the survey has dropped significantly. (Falling response rates since the pandemic are a serious issue for other key economic data sources as well.[10])

There is also scope for increases in labor force participation, including through immigration, to expand the supply of workers and ease some tightness in the labor market. Labor force participation rates (the share of the population either working or unemployed and actively looking for work) in several age groups are not fully back to their pre-pandemic levels. That includes people in their prime working years (ages 25 to 54), although it is close for this group.

Much about the labor market has changed as a result of the pandemic disruptions, but it is worth remembering that the pre-pandemic economy had low inflation along with high labor force participation (with room to improve), low unemployment, and in 2018 and 2019 rising real wages. Unfortunately, even in those boom years, the labor share of business income was low compared to historical levels. The goal is to maintain low unemployment and return to low inflation, while workers experience significant and sustainable real wage gains. The labor market has moved toward that goal but more progress is needed; what’s not at all clear, however, is whether further rate hikes at this point make this outcome more likely or less likely.

When the Fed in early 2022 began tightening monetary policy by raising interest rates,[11] some Fed officials thought a “soft landing” might be possible, in which economic growth slowed and tighter monetary policy cooled firms’ hiring intentions but did not lead to substantial layoffs. In such a scenario, economic growth would slow and new entrants to the labor force might have longer job searches, but a full-blown recession in which economic activity contracted and unemployment rose sharply would be avoided.[12]

The Fed backed away from this hope as inflation continued to rise through the first half of 2022, but the recent behavior of the economy bears some resemblances to that scenario. Nevertheless, after the December meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC),[13] and again in February, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell stated the FOMC’s position: “We continue to anticipate that ongoing increases in the target range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.” While acknowledging that recent developments are encouraging, Powell stated that “we will need substantially more evidence to be confident that inflation is on a sustained downward path.”[14]

Such a path carries with it the risk of inducing a recession. The December Summary of Economic Projections of FOMC participants (released before fourth-quarter 2022 data were available) shows neither a soft landing nor a recession. Economic growth was projected to be 0.5 percent (fourth quarter to fourth quarter) in both 2022 and 2023, and the average unemployment rate in the fourth quarters of 2023 and 2024 was projected to be 4.6 percent. These are not recession projections, but they are far from a soft landing. A rise in the unemployment rate would mean many more workers and their families would have limited means to weather a spell of joblessness and would risk increased hardship.

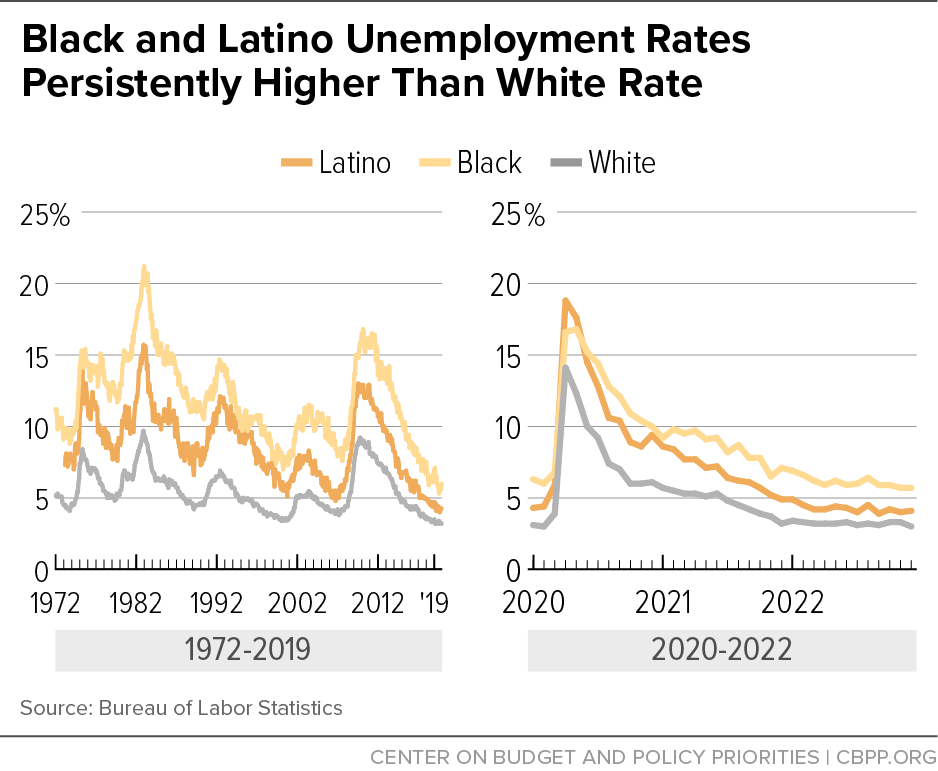

A rise in unemployment would likely be particularly hard on Black and Latino workers. A long history, and the continuing reality, of structural racism and discrimination in employment and other areas has contributed to persistently higher rates of unemployment for Black and Latino workers than for white workers. Since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began collecting unemployment data by race in the early 1970s, Black unemployment has on average been roughly twice as high — and Latino unemployment roughly one and one-half times as high — as white unemployment, whether the economy was expanding or contracting. (See Figure 4.)

Until the Great Recession, Black unemployment in the best of times was not much better than white unemployment in the worst of times. Significant racial disparities have persisted since then, but Black, Latino, Asian, and white unemployment rates are all back to being close to their pre-recession rates in the recovery from the pandemic recession. Historically, Black workers have been the “last hired and first fired” and would suffer the most harm in a recession.

The Fed’s rationale for tightening monetary policy is a desire to keep expectations of future inflation “anchored” at close to its 2 percent target.[15] What the Fed has wanted to avoid is above-target current inflation getting built into expectations of future inflation, which could trigger a cycle of anticipatory wage and price increases that could only be broken by very tight monetary policy and a severe recession, as happened under then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker in the early 1980s.[16] In the Fed’s view, convincing people of its willingness to “do what it takes” to bring down current inflation is necessary to keep inflation expectations anchored. As mentioned earlier, however, longer-term inflation expectations have remained anchored.

Powell makes the following risk management argument for continuing to tighten: if the Fed overtightens monetary conditions and the economy weakens too much, the Fed has the tools to reverse course and support the economy. But if the Fed doesn’t get inflation under control because it didn’t tighten enough or began to loosen too soon and inflation becomes entrenched, the employment costs of getting it back down likely will be much higher.

The counter, of course, is that because of the lags in the response of economic activity to changes in monetary policy, the economy could be well into a recession before an easing of monetary policy would begin to support economic activity and employment. The result would be rising unemployment and significant hardship — outcomes that will likely fall disproportionately on low-paid workers, particularly Black and Latino workers, and on those who have little in savings to fall back on. When the economy weakens, businesses and individuals see unemployment rise and, concerned about what the economic future holds, pull back on spending and investment, further weakening demand and economic growth and leading to further increases in unemployment.

The prospect of rising unemployment and recession is particularly concerning in our current political landscape, in which it is not clear that Congress would agree to use fiscal policy to respond to a weakening economy. A look at recent examples is instructive. A Democratic Congress and President George W. Bush reached a bipartisan agreement to provide modest relief in 2008 in response to the recession. But in early 2009, President Obama and congressional Democrats received no Republican support in efforts to shore up an economy by then in freefall. The result was a unilateral Democratic effort that, while highly successful in providing critical relief to households and the economy, proved to be undersized, leading to a weaker recovery than would have been possible with more robust action.

Democrats at the time controlled the White House and both chambers of Congress until the 2010 elections. With the return of divided government, enacting significant additional stimulus measures became impossible. With divided congressional control today, legislation can only be enacted through bipartisan action. Early in the pandemic in 2020, a divided Congress did reach bipartisan agreement on important and robust relief measures that President Trump signed into law. But after President Biden took office, Republican interest in negotiating around relief measures waned considerably. The American Rescue Plan, a crucial piece of the recovery from the pandemic recession, received no Republican votes.

It is certainly possible that if faced with rising unemployment, Congress could reach bipartisan compromise on efforts to reduce hardship and stimulate aggregate demand. But there are serious political headwinds to such a compromise.

Absent congressional action, the only significant federal policy response to a recession would be through monetary policy, which acts more slowly and can’t target assistance to those facing real hardship.

The Fed faces a challenging task. It may not want to deviate from its public stance that it will continue tightening monetary policy until inflation is clearly on a path to stabilizing at or near its 2 percent target. But the risks and costs of precipitating a recession should play an important role in determining monetary policy going forward. The Fed can and should communicate that pauses to assess the balance of risks need not compromise its commitment to making steady progress toward its inflation goal.