Congress Should Revisit 2017 Tax Law’s Trillion-Dollar Corporate Rate Cut in 2025

End Notes

[1] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Revenue Proposals,” March 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/tax-policy/revenue-proposals. This estimate covers the 2025-2034 budget window.

[2] Patrick J. Kennedy et al., “The Efficiency-Equity Tradeoff of the Corporate Income Tax: Evidence from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” November 14, 2023, https://patrick-kennedy.github.io/files/TCJA_KDLM_2023.pdf. The $114,000 threshold for the 90th percentile appears in an earlier version of the paper, dated December 9, 2022 (Table 5, Panel A).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robert Gebeloff, “Who Owns Stocks? Explaining the Rise in Inequality During the Pandemic,” New York Times, January 26, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/26/upshot/stocks-pandemic-inequality.html.

[5] This $1.3 trillion ten-year cost estimate of reducing the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent is roughly equivalent to Treasury’s estimated $1.3 trillion revenue gain from reversing only half of the original rate cut. However, the Treasury estimate covers a more recent budget window and reflects changing economic conditions, including economic growth and inflation, that have occurred since 2017. Treasury also includes the effects of interacting provisions of the 2017 tax law and makes somewhat different modeling assumptions than JCT.

[6] Gabriel Chodorow-Reich et al., “Tax Policy and Investment in a Global Economy,” NBER Working Paper, March 2024, https://www.nber.org/papers/w32180. The authors show that even when corporate tax cuts increase investment, there are countervailing, dynamic revenue impacts. On the one hand, more economic activity could expand the tax base and therefore increase tax collections; on the other, increased investment leads firms to take more depreciation deductions, which decreases tax collections. This study concludes that these two forces nearly offset over the first ten years, such that “the total revenue effect closely mirrors the mechanical corporate effect.” In the long run, the paper projects that dynamic effects could “close roughly 20 percent of the mechanical revenue decline.” Regarding claims that the 2017 tax law would pay for itself, see e.g., Kate Davidson, “Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin: GOP Tax Plan Would More Than Offset Its Cost,” Wall Street Journal, September 28, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/treasury-secretary-steven-mnuchin-gop-tax-plan-would-more-than-offset-its-cost-1506626980.

[7] Edward G. Fox and Zachary D. Liscow, “A Case for Higher Corporate Tax Rates,” Tax Notes, Vol. 167, No. 12, June 22, 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3657324.

[8] Kimberly A. Clausing, “Capital Taxation and Market Power,” Working Paper, April 22, 2023, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4419599.

[9] Natasha Sarin and Kimberly A. Clausing, “The coming fiscal cliff: A blueprint for tax reform in 2025,” Hamilton Project, September 27, 2023, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/policy-proposal/the-coming-fiscal-cliff-a-blueprint-for-tax-reform-in-2025/.

[10] J. Baxter Oliphant, “Top tax frustrations for Americans: The feeling that some corporations, wealthy people don’t pay fair share,” Pew Research Center, April 7, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/07/top-tax-frustrations-for-americans-the-feeling-that-some-corporations-wealthy-people-dont-pay-fair-share/. See also Vanessa Williamson, “Back without popular demand: Tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations,” Brookings Institution, September 27, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/back-without-popular-demand-tax-cuts-for-the-wealthy-and-corporations/.

[11] Council of Economic Advisers, “Corporate Tax Reform and Wages: Theory and Evidence,” October 2017, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/Tax%20Reform%20and%20Wages.pdf.

[12] TPC, Table 17-0180 - Share of Change in Corporate Income Tax Burden; By Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2017, June 6, 2017, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/distribution-change-corporate-tax-burden-june-2017/t17-0180-share-change-corporate.

[13] Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “The Economic Effects of the 2017 Tax Revision: Preliminary Observations,” Congressional Research Service, updated June 7, 2019, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45736.

[14] Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke, “Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Their Shareholders,” New York University School of Law, October 27, 2020, https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/Who’s%20Left%20to%20Tax%3F%20US%20Taxation%20of%20Corporations%20and%20Their%20Shareholders-%20Rosenthal%20and%20Burke.pdf.

[15] Gravelle and Marples.

[16] William Gale and Claire Haldeman, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: Searching for supply-side effects,” Brookings, July 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/20210628_TPC_GaleHaldeman_TCJASupplySideEffectsReport_FINAL.pdf.

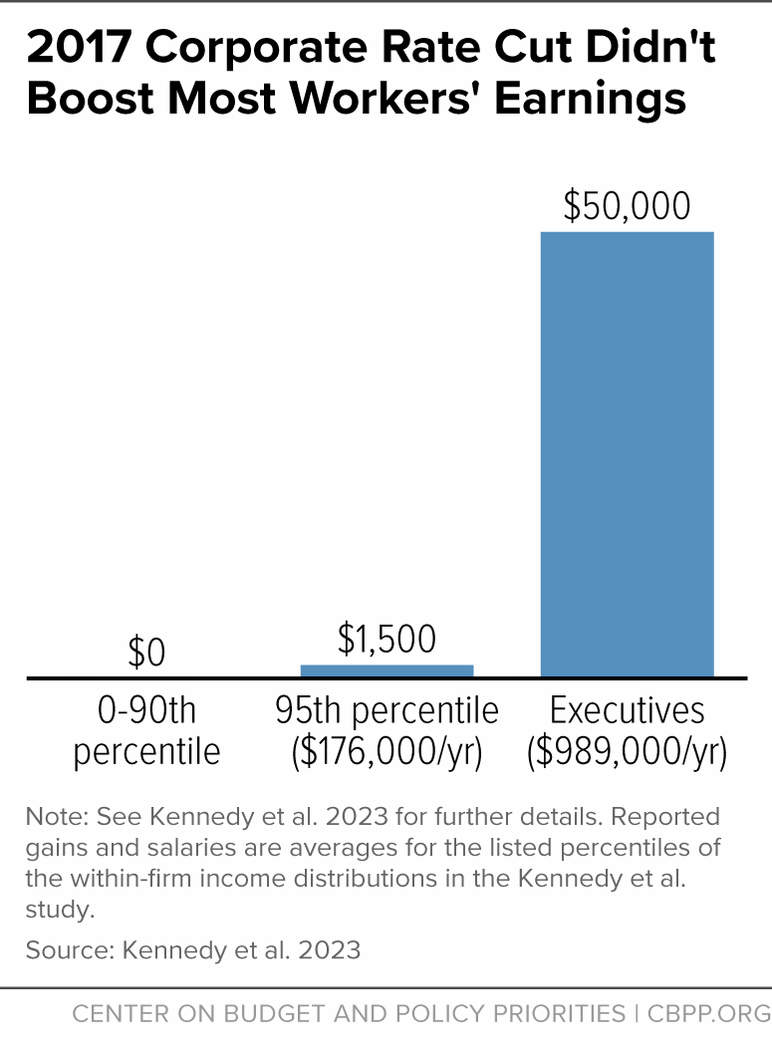

[17] The Kennedy et al. paper finds increases in sales, profits, investment, employment, and payrolls in C-corporations relative to comparable S-corporations. The employment result — a 2.2 percent relative uptick in employment at C-corporations in the study’s sample — does not include a distributional analysis of which types of workers benefited.

One limitation of the Kennedy et al. and Chodorow-Reich et al. studies is that they do not fully reflect the role of the largest C-corporations. However, the largest C-corporations comprise a significant share of the corporate tax base and may also be the firms with the most market power, meaning the behavior of these firms is both highly relevant for policymakers and potentially less responsive to corporate tax rate changes than smaller firms.

[18] The sample period is 2013-2019, and gains from the tax cut are reported in nominal dollars.

[19] Ibid. These results reflect within-firm — not economy-wide — income distributions.

[20] Gebeloff.

[21] Kennedy et al.

[22] David Mitchell, “Six Years Later, More Evidence Shows the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Benefits U.S. Business Owners and Executives, Not Average Workers,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, December 20, 2023, https://equitablegrowth.org/six-years-later-more-evidence-shows-the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-benefits-u-s-business-owners-and-executives-not-average-workers/.

[23] The productivity findings appear in the earlier version of the Kennedy et al. working paper, dated December 9, 2022..

[24] Chodorow-Reich et al. Economist Patrick Driessen argues that due to methodological issues relating to intellectual property, the Chodorow-Reich et al. study could overstate the effects of the 2017 corporate tax cuts on investment. In an earlier paper, economists Eric Zwick and Owen Zidar note that proponents’ promised investment boost from the corporate tax cuts may have come closer to materializing than predictions about wages and revenue “but was likely overstated.” Patrick Driessen, “The ‘It’ Paper on the Effects of the TCJA,” Tax Notes Federal, February 26, 2024, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-taxation/it-paper-effects-tcja/2024/02/28/7j7nd?highlight=driessen; Owen Zidar and Eric Zwick, “The Next Business Tax Regime: What Comes After the TCJA?” Aspen Economic Strategy Group, in Building a More Resilient US Economy, November 8, 2023, https://www.economicstrategygroup.org/publication/the-next-business-tax-regime-what-comes-after-the-tcja/.

[25] Jim Tankersley, “Trump’s Tax Cut Fueled Investment but Did Not Pay for Itself, Study Finds,” New York Times, March 4, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/04/us/politics/trump-corporate-tax-cut.html.

[26] Juan Carlos Suarez Serrato, “Targeting business tax incentives to realize U.S. wage growth,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, January 14, 2021, https://equitablegrowth.org/targeting-business-tax-incentives-to-realize-u-s-wage-growth/.

[27] Max Risch, “Trickle-Down Revisited,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 2023, https://www.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/2023-02/Trickle_Down_Feb14%20%281%29.pdf.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Jacob Pramuk, “GOP tax cuts will pay for themselves — but only if other changes happen too, Treasury says,” CNBC, December 11, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/12/11/treasury-department-report-says-gop-tax-cuts-will-pay-for-themselves.html.

[30] Davidson.

[31] CBO, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028,” April 9, 2018, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651.

[32] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of The Conference Agreement For H.R.1, The Tax Cuts And Jobs Act,” December 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2017/jcx-67-17/.

[33] Chodorow-Reich et al. See note 6 for a discussion of the study’s findings that despite increased investment, the corporate tax cuts led to large, nearly dollar-for-dollar revenue losses.

[34] Kennedy et al.

[35] Treasury.

[36] Laura Power and Austin Frerick, “Have Excess Returns to Corporations Been Increasing Over Time?” National Tax Journal, Vol. 69, No. 4, December 2016, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdf/10.17310/ntj.2016.4.05.

[37] Edward Fox, “Does Capital Bear the U.S. Corporate Tax After All? New Evidence from Corporate Tax Returns,” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Vol. 17, No. 1, March 2020, https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3191&context=articles.

[38] Sebastian Beer et al., “Exploring Residual Profit Allocation,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 15, No. 1, February 2023, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.20200212.

[39] The 2017 law also resulted in somewhat less generous treatment of research and experimentation costs and capital investments beginning in 2022, as well as limitations on the amount of interest that businesses can deduct. The House-passed Smith-Wyden tax bill would reinstate full expensing of domestic research and experimentation costs and capital investments and relax the limitation on interest deductions.

[40] Fox and Liscow.

[41] The study by JCT and Federal Reserve economists offers a somewhat different view. It argues that the corporate tax is roughly as progressive as the individual income tax but has a larger negative impact on economic activity, so generating less federal revenue from corporate taxes and more from individual taxes “may yield efficiency gains without sacrificing much in progressivity.” Kennedy et al. Other dimensions of equity and efficiency, however, favor a strong entity-level tax, meaning a tax that applies to business-level income.

All else equal, shifting federal tax revenue away from the corporate tax base and towards the individual income tax would further widen the gap in the tax treatment of income from capital and labor. “[M]uch of the capital income tax base is unreachable if one is limited to the individual layer of taxation,” warns UCLA economist and former Treasury Department official Kim Clausing. In a proposal to raise the corporate tax rate to 28 percent, economists Owen Zidar of Princeton and Eric Zwick of the University of Chicago explain that “a robust corporate tax is a key component of a progressive tax system that taxes capital income and reduces tax sheltering opportunities for high-earning business owners.”

Professor Clausing also notes that “The importance of market power strengthens the argument for taxing capital income at the entity level, rather than the individual level” because the corporate tax can target rents (i.e., super-normal returns) more directly than the individual income tax. Fox and Liscow explain that, as a result, the corporate tax can discourage companies from wasteful rent-seeking behavior. They conclude, “As a matter of both equity and efficiency, this entity-level tax is likely to be desirable.”

See Clausing; Zidar and Zwick; Fox and Liscow.

[42] Andrew Barr, Jonathan Eggleston, and Alexander A. Smith, “Investing in Infants: the Lasting Effects of Cash Transfers to New Families,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, April 20, 2022, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article/137/4/2539/6571263; Samantha Waxman et el., “Income Support Associated with Improved Health Outcomes for Children, Many Studies Show,” CBPP, May 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/income-support-associated-with-improved-health-outcomes-for-children-many.