Chairwoman Maloney, Ranking Member Comer, and distinguished members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Michael Leachman, Vice President for State Fiscal Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and policy institute in Washington, D.C.

I will provide an overview of the historic gains achieved by the federal government’s robust COVID-19 relief efforts, including the American Rescue Plan. I’ll then explain how the American Rescue Plan’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds, in particular, are helping states, localities, tribal governments, and U.S. Territories respond to the pandemic, assist people and businesses to recover from it, and support a stronger economic recovery. I’ll also offer some thoughts about providing federal fiscal aid to these governments in future recessions.

When COVID-19 began to rapidly spread across the United States in March 2020, the economy quickly shed more than 20 million jobs. Amid intense fear and hardship, federal policymakers responded, enacting five relief bills in 2020 that provided an estimated $3.3 trillion of relief and the American Rescue Plan in 2021, which added another $1.8 trillion. This robust policy response helped make the COVID-19 recession the shortest on record and helped fuel an economic recovery that has brought unemployment, which peaked at 14.8 percent in April 2020, down to 4.0 percent. One measure of annual poverty declined by the most on record in 2020, in data going back to 1967, and the number of uninsured people remained stable, rather than rising as typically happens with large-scale job loss. Various data indicate that in 2021, relief measures reduced poverty and helped people access health coverage, afford food, and meet other basic needs.

These positive results contrast sharply with the Great Recession of 2007-2009, when the federal response was less than one-third as large as the fiscal policy measures of 2020-2021, when measured as a share of the economy. While decried by some at the time as too large, the relief measures enacted during the Great Recession were actually too small and ended too soon. As a result, the economy remained weak for longer than necessary — and families suffered avoidable hardship. Two years after the Great Recession began, unemployment was still 9.9 percent and food insecurity remained one-third above its pre-recession level. While some of that difference stems from differences in what caused each downturn, some is clearly due to the strength of the policy response this time around.

The federal response to the pandemic was not only large but also broad in its reach and innovative in its policy approaches. In addition to funding the public health response to the pandemic, such as personal protective equipment, testing, and vaccines, the federal government took a number of steps for the first time, including providing fiscal aid directly to cities, counties, and tribal governments, whose budgets were severely challenged by the pandemic. The federal response also included more substantial fiscal aid to states and U.S. Territories than in the Great Recession.

The large, broad, and innovative relief effort has directly strengthened the recovery and reduced hardship, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and other independent analysts agree. International comparisons show that nations with larger fiscal responses to the pandemic, such as the United States, have experienced stronger growth.[1] In substantial part due to federal action:

- The recession lasted only two quarters, the shortest recession on record.

- The unemployment rate fell rapidly to 6.7 percent at the end of 2020 and to 4.0 percent today, only modestly above the low pre-pandemic level of 3.5 percent and much lower than at this point in the recoveries from the last three recessions.

- The number of people with annual income below the poverty line, after accounting for government assistance, fell by 8 million in 2020, the largest amount on record in data going back to 1967. Monthly estimates showed poverty continued to decline from 2020 to 2021.

- The number of adults reporting that their household did not get enough to eat in the last seven days declined in 2021 after peaking in late 2020. A more detailed annual measure of food insecurity suggests that food hardship was largely kept in check in 2020.

- Health insurance coverage remained roughly stable even though millions of people lost employer-provided health insurance. Medicaid enrollment increased by over 12 million from February 2020 to July 2021 due to relief provisions that provided continuity of coverage, and the Affordable Care Act marketplace enrollment grew by more than 3 million from 2020 to 2022.

- Despite significant administrative challenges, millions of people received jobless benefits because of temporary eligibility expansions and tens of millions received increased benefits. Jobless benefits kept 5.5 million out of poverty in 2020, Census data show.

- There was no surge in evictions even though millions of people were behind on their rent. Over 3.2 million households received emergency rental assistance from January to November 2021 to help them with past-due and current rent bills, forestalling eviction for many.

Surveying the impacts on hardship, the University of Michigan’s H. Luke Shaefer concluded, “This is the best, most successful response to an economic crisis that we have ever mounted, and it is not even close.”[2]

The economic fallout from the pandemic was especially severe for workers in low-wage sectors, such as restaurants and hospitality, in which people of color and women are overrepresented. Black and Latino people were already more economically vulnerable due to structural racism and the history of discrimination in employment, housing, education, and other areas. This meant that many elements of the pandemic response that targeted those with the greatest need had particularly large, positive impacts on them.

Currently, policymakers and others are focusing significant attention on the recent rise in inflation, which stretches families’ budgets — although rising wages, particularly at the low end of the wage scale, have helped offset some of the impacts. A number of factors are driving inflation, including pandemic-related changes to the types of goods people are buying and challenges in increasing production amid an ongoing pandemic in some sectors. While high inflation has lasted longer than many analysts predicted, the Federal Reserve has tools to bring it down. Lowering inflation is important, but the current strong job and economic growth have been critical to mitigating the hardship that people would have faced in the absence of a strong policy response to an unprecedented crisis.

The COVID relief effort teaches important lessons. It shows that a rapid, robust, and broad-based response can greatly speed recovery, reduce suffering, and mitigate disparities. As Mark Zandi and other economists at Moody’s Analytics conclude in a new analysis, “policymakers’ decisiveness in pushing forward with substantial government support has been an economic gamechanger.” They estimate that, “the [U.S.] economy is currently on track to recoup all of the jobs lost during the pandemic recession by late this year. Without government support, this milestone would not have been achieved until summer 2026” and “[l]ow-wage workers, which have suffered most financially during the pandemic, would have been set back even further.”[3]

Federal aid to state and local governments, territories, and tribal governments is important during any economic downturn. Their revenues typically fall during recessions since people lose income and consume less, and their costs typically rise since more people need public assistance. Unlike the federal government, states and localities must balance their budgets every year; without federal aid during recessions, they must cut services or raise revenue (or both), which can weaken the economy further.

After the Great Recession hit over a decade ago, Congress provided fiscal relief to states that was important, but — like the federal fiscal response to the recession generally — was too small and ended too soon. The state fiscal aid, which included an increase in the share of Medicaid funding that the federal government would pay and aid primarily aimed at education, covered only about a quarter of state budget shortfalls and ended at a time when states still faced large budget shortfalls.[4] As a result, states laid off hundreds of thousands of workers during the recession and its aftermath and cut services at a time when the need for those services was particularly high. Cities, counties, and tribal governments got no direct fiscal aid at all.

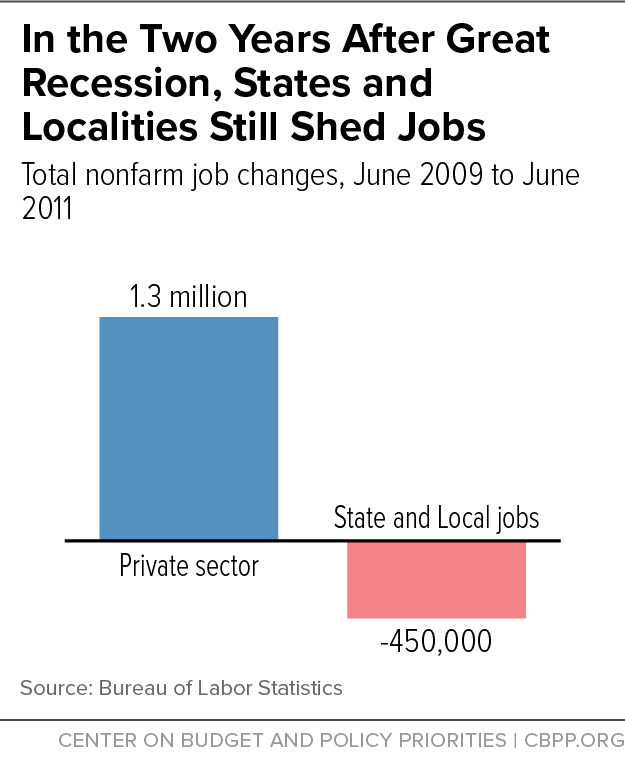

As a result, the economy’s recovery from the Great Recession was significantly slower than it needed to be. Over the first two years after the recession officially ended, the private sector added about 1.3 million jobs, but states and localities cut 450,000 jobs. (See Figure 1.) With too little federal help, states and localities were effectively still in recession, holding back the rest of the economy’s growth.

Plus, the state and local service cuts were so deep that they were still with us when the pandemic hit. For instance, heading into the pandemic, our schools had 77,000 fewer teachers and other school workers than when the Great Recession hit, but about 1.5 million more kids to educate. State and local public health departments shed at least 38,000 jobs and slashed their spending by between 16 and 18 percent per capita.[5] We paid a price for that when the pandemic hit.

In its immediate budgetary effects, the pandemic hit like other downturns, causing state, local, tribal, and territory revenues to collapse and costs to rise sharply. Without federal aid, the pandemic would have forced deep cuts in state and local services at a time when increased supports — including public health measures to respond to the pandemic — were needed.

The CARES Act included $150 billion in aid for states, local governments with populations over 500,000, tribal governments, and U.S. territories — which they could use only for new costs incurred due to the public health emergency through the end of 2020, and not to make up for revenue losses.[6] The Families First Coronavirus Response Act increased the federal share of Medicaid funding, a crucial step given the rapid surge in people needing health coverage; the added Medicaid dollars strengthened states’ overall fiscal picture while protecting coverage for millions of people.

These funds helped meet increased needs but left many state, territorial, tribal, and local governments unable to meet remaining challenges. Even with the CARES Act aid, the number of state and local employees fell at a time of increased need for public services, dropping by 1.2 million or 6 percent between February and December 2020. Many medium-sized and small localities, left out entirely of the CARES Act, continued to struggle.

The American Rescue Plan provided $350 billion in more flexible aid to help states, local governments of all sizes, tribal governments, and U.S. Territories respond to the pandemic. The law’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) provided:

- For the first time, direct, flexible fiscal aid to mid-sized and small cities and counties.

- Much needed additional help to tribal governments and U.S. Territories, which were hit particularly hard by the pandemic.

- Federal aid that states and other governments could use to provide existing government services undercut by pandemic-induced revenue losses, giving them a hedge against expected shortfalls, and helping them rehire workers and reverse spending cuts from earlier in the pandemic.

- Funds for responding to the evolving virus and its negative economic impacts on people and businesses, offering premium pay to essential workers, and investing in needed broadband, water, and sewer infrastructure projects, consistent with the Act’s goal of seeding a strong recovery.

- Funds that these governments can obligate through the end of 2024 and finish expending through the end of 2026. Treasury Department guidance has strongly encouraged recipients to use the funds to address racial and economic inequities that predated the pandemic and then made the crisis worse, and to address pandemic-induced problems that may take years to unravel such as lost learning time for children and the increased prevalence of mental illnesses.

As a result, this time around states, localities, territories, and tribal governments are contributing to the economic recovery and are well-positioned to leave the country more prepared when the next downturn hits.

States are using the funds to limit the pandemic’s harm and help their residents recover. As of a few weeks ago, when state legislative sessions were just beginning, states had appropriated 72 percent of the funds they received so far.[7] Many states are now developing plans to use much of the remaining funds. The limited data we have about local governments suggests that they also have allocated most of their funds. Reports by the most populous cities and counties document that, even as early as July 2021, they’d already allocated more than half of the funds then available, most commonly to make up for lost revenues.[8]

Nearly a quarter of state funds has gone to cover existing government services that pandemic-induced revenue losses made difficult to provide. Those funds have made it easier for states to hire school workers, health care staff, and others whose jobs were lost when the pandemic hit. Nearly another quarter of state funds has gone to health care and human services for people affected by the pandemic. For example, Utah appropriated funds for a system to provide booster shots, California revamped its youth mental health system to provide better care to more children, and Virginia raised wages for mental health workers. Another quarter has gone to help affected businesses and for economic development and infrastructure. For example, Wisconsin spent funds supporting businesses in communities most affected by the downturn and Delaware, Colorado, and other states invested in expanding broadband, consistent with a goal of the Recovery Funds to help seed a stronger recovery. And most of the rest has gone to shore up state unemployment trust funds, which were hit hard after the pandemic.[9] Unfortunately, some states have used the funds in ways that are inconsistent with the law’s spirit. Alabama, for example, devoted nearly one-fifth of its funds to build new prisons.

Many states are also considering tax cuts. The American Rescue Plan expressly forbids using the funds for tax cuts,[10] but states can use their own funds for that purpose. While the Recovery Funds improved state finances and thus may have indirectly helped some policymakers consider tax cuts, many states likely would have considered tax cuts this year without the Recovery Funds, for reasons that vary by state; policymakers in some states were trying to eliminate or sharply reduce income taxes even before the pandemic.[11] Some states are considering permanent income tax cuts — a longstanding goal of some conservative policymakers and interest groups — even though the federal recovery funds are temporary. (Conservatives pursued tax cuts after the Great Recession as well, though the federal government provided much less state fiscal aid then.)[12] Other states are considering one-time tax cuts to reduce household costs.

Localities, territories, and tribal governments have used the Recovery Funds productively. For example, Pittsburgh used some of the funds to save 600 jobs slated for elimination and committed to providing free Wi-Fi in community centers, among other uses.[13] St. Louis set aside funds for a mobile vaccination effort, a jobs program for youth from low-income families that had been especially affected by the pandemic, and efforts to help house homeless people and reduce evictions.[14] Tribal nations are especially vulnerable to COVID-19’s health risks and the pandemic sharply reduced the revenues of tribal governments that rely on tourism and casinos,[15] but the Recovery Funds have transformed tribal governments’ ability to respond to the pandemic and help tribal members recover. The Navajo Nation, for example, is using Recovery Funds for broadband and water projects, support for tribal businesses, care for COVID-19 patients, and burial assistance for the families of COVID victims, among other uses.[16] U.S. territories also face especially difficult conditions in fighting and recovering from the virus; Puerto Rico has already allocated some 83 percent of its Recovery Funds for initiatives such as COVID-19 tracking efforts, support for affected businesses, premium pay for essential workers, and mental health programs.[17]

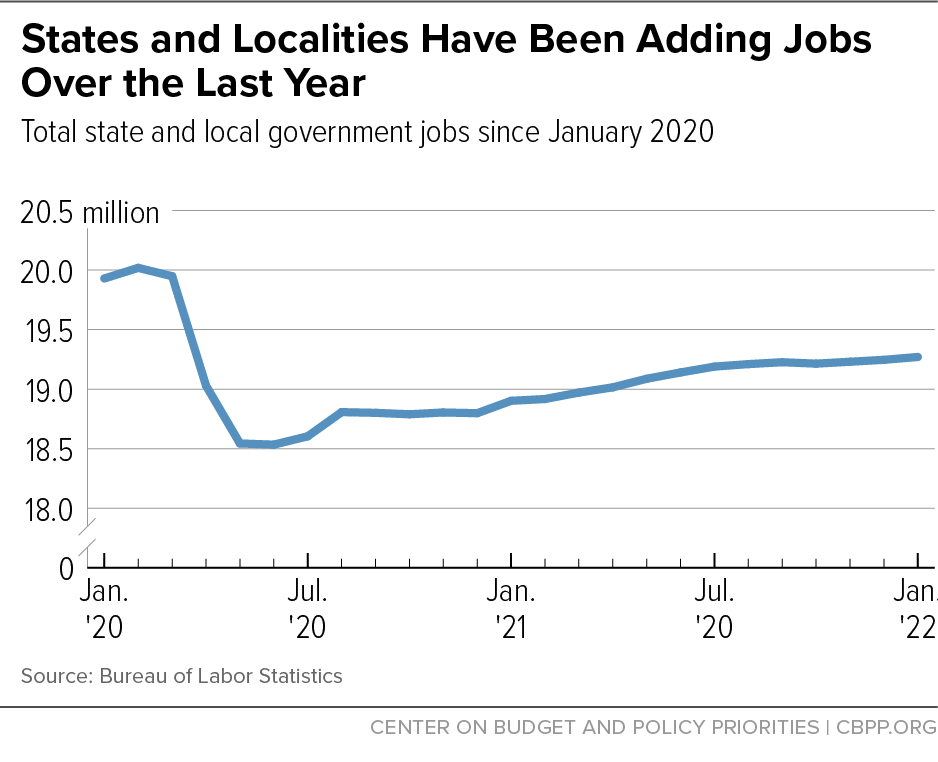

The aid is helping states and localities rebuild their workforce. In the fall of 2020, state and local hiring stalled. That December, states and localities had 1.2 million fewer jobs than before the pandemic, a decline of more than 6 percent. Since then, states and localities have hired 470,000 more workers. (See Figure 2.) And that figure likely would be higher if many employers, especially schools, were not facing hiring challenges. By contrast, without the Recovery Funds and earlier pandemic aid, states and localities would have laid off even more workers. An analysis by Mark Zandi and his colleagues at Moody’s estimates that state and local jobs would still be down by about 2 million jobs, holding back the economy as after the last recession.[18]

The last two economic crises provide important lessons for the design of state and local fiscal recovery funds in future downturns. Federal aid to states and territories in response to the Great Recession was too small (covering only one-quarter of state budget shortfalls) and ended too soon, and local and tribal governments received no federal aid. As a result, layoffs and deep, recession-induced spending cuts by states and other governments weakened the recovery. In the current crisis, federal aid to states, localities, territories, and tribal governments was far more robust and, with the Recovery Funds, policymakers gave them more time to use it. This was particularly appropriate since the pandemic produced a highly uncertain and still-unfolding economic and fiscal challenge, and many of its harmful impacts may last longer than the effects of a more typical recession.

In a future crisis, policymakers should avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession’s fiscal aid response and err on the side of ensuring that states and other governments have enough aid to meet the needs of residents and businesses. Policymakers can consider ways to link the amount of aid and its duration to economic conditions, though doing so presents design challenges and policymakers should avoid providing less than what’s needed. Policymakers should require states and other governments to spend sizeable portions of the aid in ways that particularly help low-income people, communities of color, and others especially likely to be harmed by an economic crisis. They also can consider additional ways to limit the use of funds, again recognizing the challenges in striking a reasonable balance between giving states and other governments flexibility and ensuring that funds aren’t used in problematic ways. Finally, policymakers should continue to support the fiscal health of tribal governments during future recessions; the first-ever fiscal aid during this downturn was a historic advance and sets an important and positive precedent.