To support sound budget policies, the level of federal revenue — measured as a percent of the nation’s economy, or gross domestic product (GDP) — needs to increase over previous and currently projected levels. Our nation’s budget policies reflect our approach to two fundamental questions: what and whom will our country invest in and support, and how will we pay for those investments? Our current approach is one of low investment and support for people and communities relative to other wealthy nations, coupled with even lower revenue. This has led not only to a fiscal deficit, with federal debt growing more quickly than GDP, but also an investment deficit.[1]

To meet our commitments to seniors, make high-value investments that will improve well-being and broaden prosperity, and improve our fiscal outlook, we must raise more revenue. Simply put, we cannot meet 21st-century needs with past levels of revenue. As a first step, policymakers should use the scheduled expiration of most provisions of the 2017 tax law in 2025 as an opportunity to bolster the revenue base, not erode it by failing to pay for any tax cuts that are extended and potentially adding still more tax cuts for corporations and high-income households on top.[2]

Specifically, higher revenue is needed to address three challenges:

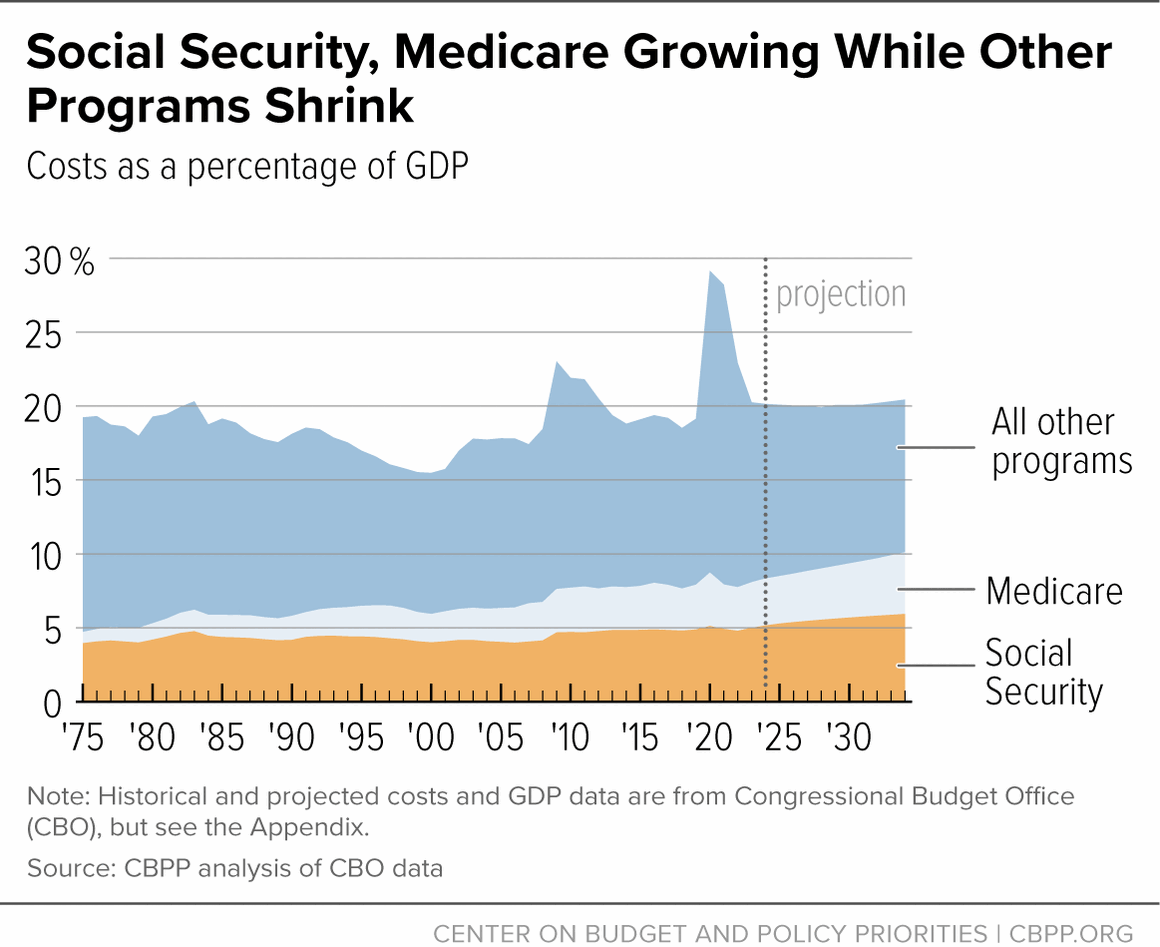

Meeting long-standing retirement and health care commitments to seniors. Budget needs are growing simply because the increasing number of baby boomers in retirement increases the costs of Social Security and Medicare. Costs for these two programs are growing faster than the economy and are projected to continue doing so.

The demographics underlying this upward budgetary pressure have been understood for decades — the results are no surprise. Indeed, cost growth for Social Security and Medicare has been slower than the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicted in 2010. Federal costs outside of these two programs are projected to grow more slowly than the economy, but this will not completely offset the demographic shift propelling the growth of Social Security and Medicare. (See Figure 1.) To finance our commitments to current and future seniors, we will need to raise more revenue.

Making high-value investments that improve well-being and broaden opportunity. Underinvesting in people, communities, and the building blocks of the U.S. economy increases poverty and hardship, worsens racial and ethnic inequities, shortchanges opportunity, and restrains economic growth.

For example, child poverty is higher in the U.S. than in other similarly wealthy countries due to our weaker support for families with children. Temporary policies enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic produced a historic decline in child poverty and narrowed differences in poverty rates by race and ethnicity, but those gains disappeared when the measures expired. Investing in children has long-term payoffs for the entire country, and that means our under-investment is harming the nation’s potential.

Investments in this and other areas — including investments to bring down the high cost of housing and child care for families, address climate change, expand access to higher education, improve our infrastructure, and support research and technological advances — all could yield significant short- and long-term benefits to people, communities, and the economy as a whole. But they will require more revenue.

Managing the future risks associated with higher debt. Policymakers should consider the risks associated with a federal debt that’s growing faster than the economy and is projected to continue doing so. While there is no consensus among economists as to what level of debt relative to the size of the economy (known as the debt ratio) will cause significant economic harm, higher debt ratios increase risks to the economy.

At the same time, policymakers must weigh the uncertainty of those risks against the more certain, damaging consequences of underinvestment in public services and the economy, which include higher poverty, reduced health and well-being, and limited opportunity. They can best manage these risks by raising sufficient revenue both to finance investments today and to improve our long-term fiscal outlook.

Some critics argue that increasing revenue slows economic growth. But research doesn’t support the conclusion that countries with higher levels of revenue have experienced lower economic growth over time. Studies have produced conflicting findings, likely because many factors affect growth — including the type of tax, economic conditions, monetary policy, the time frame examined, and importantly, what the funds are used for. Revenue is used for a range of spending and investment that itself can both improve well-being and bolster growth.

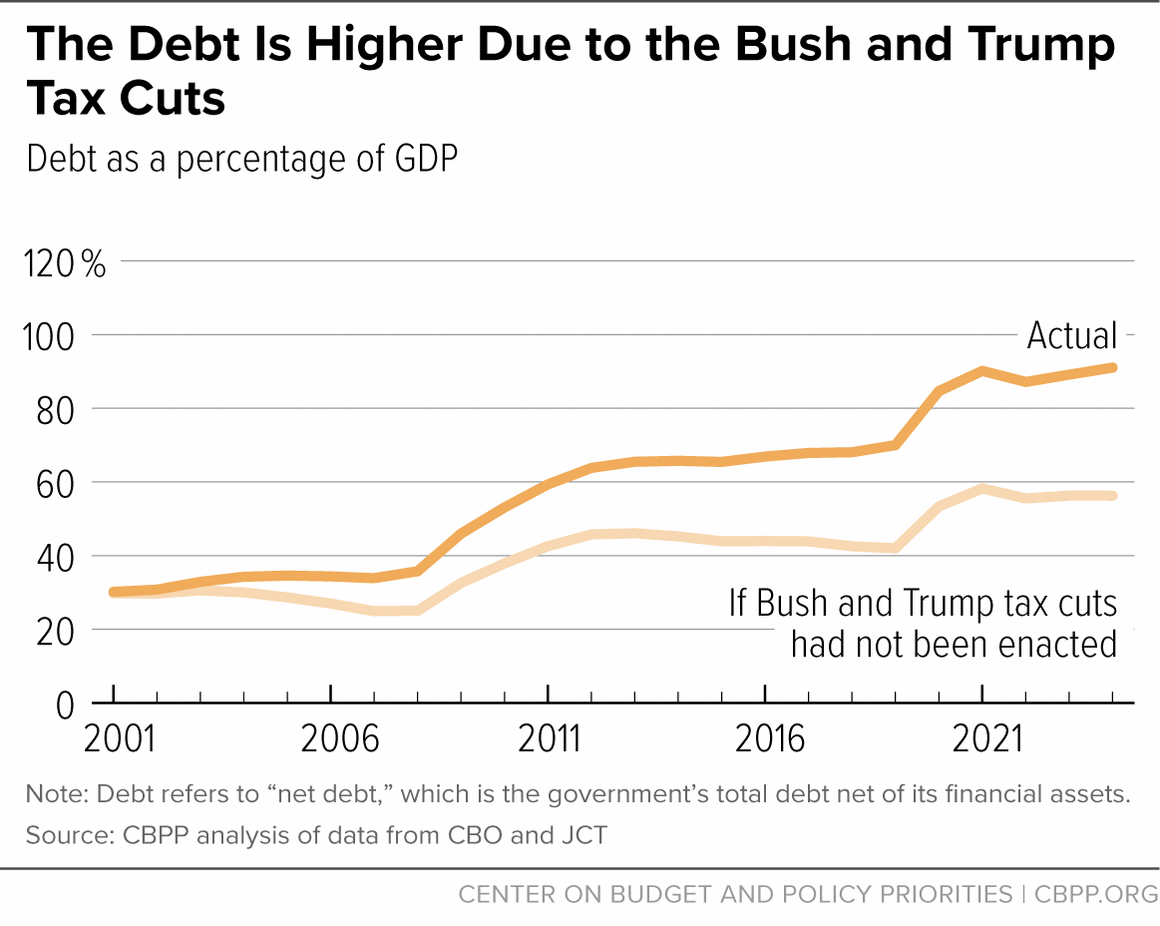

Some critics also argue that the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges are caused by overspending and thus should be addressed by cutting programs rather than raising revenue. This argument ignores the very substantial costs in deficits and debt caused by the Bush and Trump tax cuts. Absent those tax policies, deficits and debt would be much lower. And in any case, those critics have been unable or unwilling to show how the budget can be cut to achieve their fiscal goals. Budget proposals claiming to embrace that approach have combined some specific, extreme, and damaging program cuts with large additional cuts that are generally unspecified.[3]

The most recent House Republican budget resolution, for instance, called for $9.3 trillion in program cuts over ten years, but almost half of the cuts were unspecified. The specified cuts, which targeted health care and programs that help people with low incomes afford the basics, would drive up poverty and hardship and the number of people without health coverage. The unspecified cuts would require, among other cuts, massive disinvestment from the part of the budget that funds a broad range of public services, such as national parks, child care, education, scientific and medical research, and veterans’ health care. While some reasonable savings can be achieved in certain areas, such as by ending inefficient subsidies, they are far less than these extreme proposals call for, and far less than the amounts required to address the needs discussed in this report.

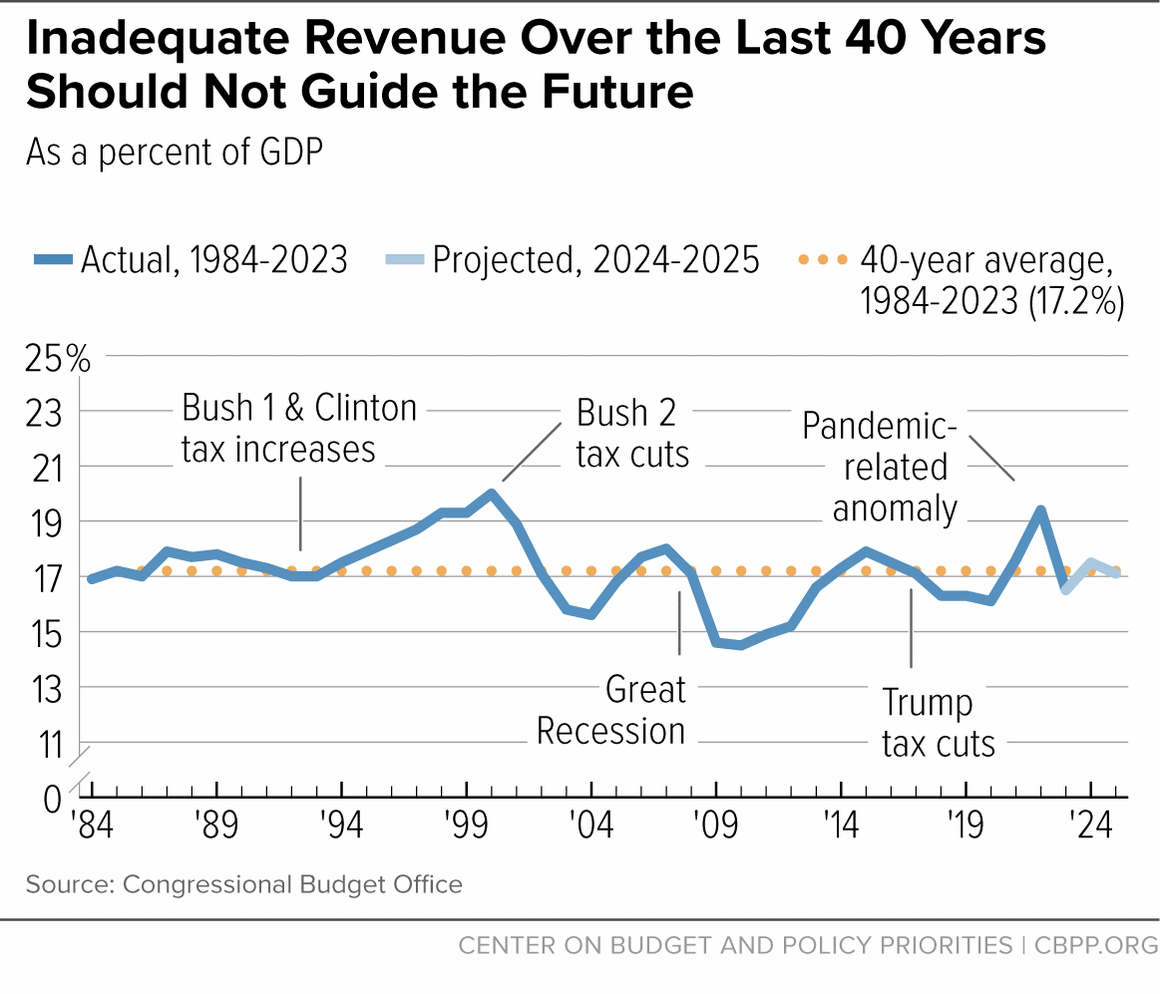

Similarly, some argue that revenue today (relative to the economy) should not be allowed to exceed historical levels, as if they represent an inevitable or natural constraint on revenue. But a backward-looking benchmark is of little use in guiding policies designed to meet current and future needs and a country with far different demographics than decades ago.

In 2024, CBO estimates that revenue will be 17.5 percent of GDP — roughly equivalent to the average over the past 40 years and close to the level in 1984. (See Figure 2.) But the country today is very different. For example, 40 years ago members of the baby boom generation (those born between 1946 and 1964) were in or still approaching their “prime working years;” today they are in the “prime retirement years,” with all but the very youngest now eligible for Social Security. And over the next 40 years, this aging trend will continue. By 2064, the share of the population over age 65 is projected to reach 22.7 percent, or nearly double the 11.6 percent share in 1984. Similarly, the dangers and challenges of climate change are more dramatic and urgent than they were 40 years ago, demanding more action today and in the future. And in 1984 we did far less than we do today to reduce child poverty, invest in child care, or ensure that people without health coverage through their jobs have access to health coverage.

In short, 21st century revenue needs are much different from those in the 1980s.

It is notable that policymakers did not let revenue levels from the first half of the 20th century dictate those of the second half. Federal revenue averaged only about 4 percent of GDP from the beginning of the last century to the beginning of World War II. But during the second half of the century, when our defense needs were notably greater and key social insurance costs (such as Social Security and public support for health insurance for seniors) emerged or began to grow, federal revenue averaged more than 17 percent of GDP. It should also be noted that economic growth was faster in the second half. The past should not bind the present or future.

Moreover, revenue levels from the past four decades were insufficient even then; the debt ratio more than doubled over that period, even before the pandemic. Despite some progress in recent decades, we invest notably less than other wealthy countries in children, families, and workers — including less in child care, paid leave, and financial help to families — and we have significantly more people without health coverage.[4] Counting all levels of government, the U.S. collects only about two-thirds as much revenue as other wealthy countries such as those in the European Union, relative to the size of the economy. Addressing our underinvestment in children, workers, and access to health care, as well as other challenges such as climate change and aging infrastructure (the result, in part, of underinvestment over past decades), will require making greater investments in the future than in the past.

Despite rising costs due to the aging of the baby boom generation and our investment deficit, policymakers have enacted tax cuts in the past two decades that have eroded the revenue base. This has undermined investments and driven up deficits and debt, increasing future economic risks.

Tax cuts enacted during the Bush and Trump administrations have substantially increased the nation’s deficits and debt. We estimate that if the Bush tax cuts and their extensions and the 2017 Trump tax cuts had not been enacted, the deficit would be less than half its current size, and the debt ratio would be considerably lower as well: 56 percent of GDP in 2024, compared to the actual 91 percent.[5] (See Figure 3.)

The individual and estate tax provisions of the 2017 tax cuts are scheduled to expire in December 2025. Extending these tax cuts without offsets would cost about $4 trillion over ten years. Allowing many of these provisions to expire, and completely offsetting any extensions with other revenue increases, is an essential first step toward rebuilding the revenue base.[6]

Even with this step, revenue in the next decade would remain below the levels of the late 1990s as a percent of the economy and below the levels of nearly all of our peer countries. Most importantly, revenue would still be well short of what is needed to accommodate the costs of an aging population and to manage our long-term fiscal challenges, let alone address our investment deficit. Additional revenue-raising efforts will therefore be needed.

These revenue increases should be progressive, which is particularly appropriate given that the nation’s income in recent decades has grown increasingly unequal. Typical middle-income families with children had almost 50 percent more income after taxes in 2019 than such families had in 1984, after adjusting for inflation. But among the top 1 percent of households, their already disproportionate incomes grew three times as fast over that period: almost 150 percent. Indeed, by 2019, the top 1 percent had annual incomes averaging $1.7 million, almost 20 times that of typical middle-income families with children.[7] Revenue-raising efforts should therefore focus on those who have gained the most over the last four decades, while new investments should focus on solving national problems and expanding opportunity.

The United States is a significantly wealthier nation than it was in 1984 and can afford to devote a greater share of its resources to addressing these challenges. It is among the world’s richest countries on a per-person basis;[8] per-person income is twice the level it was four decades ago, after adjusting for inflation, and per-person wealth has grown even more, rising 270 percent.[9] Moreover, CBO projects that over the next 30 years, inflation-adjusted per-person income will rise by another 46 percent.[10] Growing income and wealth means that even if revenue rises somewhat faster than GDP over time, the after-tax levels of inflation-adjusted income and wealth will also continue to grow. And the investments supported by that revenue will themselves improve well-being.

In short, we can afford to raise revenue and invest in people, communities, and the economy to strengthen the country and create a more broadly shared prosperity.