- Home

- Poverty And Inequality

- Executive Summary: More Relief Needed To...

Executive Summary: More Relief Needed to Alleviate Hardship

Households Struggle to Afford Food, Pay Rent, Emerging Data Show

As Congress begins considering a new relief package, likely the last before the election, emerging data show that a large and growing number of households are struggling to afford food and that millions of households are behind on rent, raising the specter that evictions could begin to spike as various federal, state, and local moratoriums are lifted. The next package should both extend the relief measures that are working but are slated to end well before the crisis abates and address the shortcomings and missing elements in the relief efforts to date.

Hardship, joblessness, and the health impacts of the pandemic itself are widespread, but they are particularly prevalent among Black, Latino, Indigenous, and immigrant households. These disproportionate impacts reflect harsh inequities — often stemming from structural racism — in education, employment, housing, and health care. Black, Latino,[1] and immigrant workers are likelier to work in industries paying low wages, where job losses have been far larger than in higher-paid industries. Households of color and immigrant families also often have fewer assets to fall back on during hard times. Immigrant households face additional unique difficulties: many don’t qualify for jobless benefits and other forms of assistance, and those who do qualify for help often forgo applying, fearing that receiving help will make it harder for them or someone in their family to attain or retain lawful permanent resident status (also known as “green card” status) in the future.

Emerging Data Show Sharp Rise in Hardship

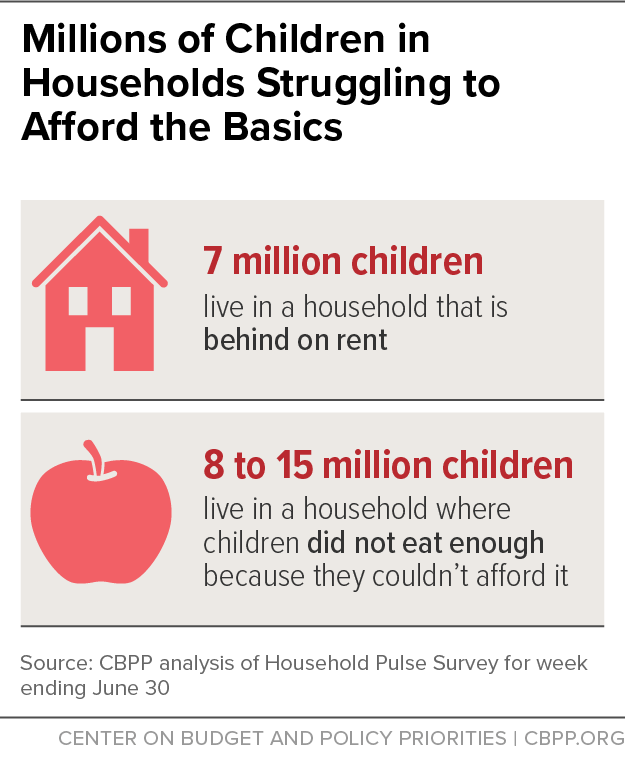

The Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Survey, launched in April, provides nearly real-time data on how the unprecedented health and economic crisis is affecting the nation. Data from this and other sources, such as unemployment data from Census’ Current Population Survey and the Department of Labor, show that tens of millions of people are out of work and struggling to afford adequate food and pay the rent. The impacts on children are large. (See Figure 1.)

- Difficulty getting enough food. Data from several sources show a dramatic increase in the number of households struggling to put enough food on the table. About 26 million adults — 10.8 percent of all adults in the country — reported that their household sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat in the last seven days, according to the Household Pulse Survey for the week ending July 7. The rates were more than twice as high for Black and Latino respondents (20 and 19 percent, respectively) as for white respondents (7 percent). And 10 to 19 percent of adults with children reported that their children sometimes or often didn’t eat enough in the last seven days because they couldn’t afford it, well above the pre-pandemic figure. This translates into an estimated 8 to 15 million children who live in a household in which the children were not eating enough because the household couldn’t afford it.

- Inability to pay rent. An estimated 13.1 million adults who live in rental housing — 1 in 5 adult renters — were behind on rent for the week ending July 7. Here, too, the rates were much higher for Black (30 percent) and Latino (23 percent) renters than white (13 percent) renters. Renters who are parents or otherwise live with children are more than twice as likely to be behind on rent compared to adults not living with anyone under age 18. Some 7 million children live in a household that is behind on rent.

- Unemployment. The unemployment rate jumped in April to a level not seen since the 1930s — and still stood at 11.1 percent in June, higher than at any point in the Great Recession. Some 15.4 percent of Black workers and 14.5 percent of Latino workers were unemployed in June, compared to 10.1 percent of white workers. Unemployment has also risen faster among workers who were born outside the United States (this includes individuals who are now U.S. citizens) than U.S.-born workers. The June data predate the sharp rise in COVID-19 cases in recent weeks that has led some states and localities to reimpose selected business restrictions and raised concerns among consumers, employers, and workers about the health risks of many activities.

Hardship is high among families for varied reasons. Many have lost jobs or seen their earnings fall. While many jobless adults qualify for unemployment benefits, some do not. For example, those who were out of work prior to the pandemic often do not qualify for jobless benefits. This includes those who left employment because they were ill or needed to care for a new baby or ill household member and those who lost employment during the normal labor market ups and downs that occur even during good times. It also includes people who recently completed schooling or training and now can’t find a job. Households are also facing rising food prices and higher costs as children are home and missing out on meals at school and in child care and summer programs. And with widespread job losses, getting help from extended family members and friends can be more difficult.

Most Effective Relief Measures Target Struggling Households

Relief measures should be designed to reduce hardship so households can pay rent, put food on the table, and meet other basic needs and to boost the economy by creating a “virtuous cycle” in which consumers can spend more, which helps the businesses where they shop stay in business and keep their workers employed, which in turn helps those workers maintain their own spending.

In a traditional recession, the relief measures most effective at boosting the economy are those that put money into the hands of struggling families — because they are most likely to spend the funds rather than save them — and provide fiscal relief to states and localities so they do not have to cut jobs and spending in areas like education, transportation, services for struggling individuals, and public works, which worsens slowdowns and hurts residents.

In this recession, measures targeted on struggling households are even more essential. That’s partly because the economic fallout from the pandemic is so severe, with the number of private and government jobs falling by nearly 15 million between February and June. Without robust relief, evictions and hunger will increase, with long-lasting health and other impacts for many children and adults. It’s also because consumer demand won’t fully return to pre-pandemic levels until the virus itself is brought under control and people feel that it’s safe to re-engage fully in the economy. The measures that will pump significant resources into the economy overall are those that help struggling families make ends meet.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (Families First Act hereafter) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, both enacted in March, included important measures to shore up household incomes and reduce hardship, including expanded unemployment benefits, direct stimulus payments through the IRS, increased nutrition benefits for some SNAP recipients, and modest fiscal relief to states and localities. Early evidence suggests that these measures have made an important difference in helping lower-income families pay their bills. A study by Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues at Opportunity Insights, for example, found that while spending fell sharply for both high- and low-income consumers early in the crisis, it rose back to near pre-crisis levels for low-income consumers when various relief measures kicked in. (By contrast, spending remained lower among higher-income households since more of their spending is discretionary and they were limiting their activities due to both the health risks and business closures.)

However, the relief measures enacted so far are temporary even though the economic fallout from the crisis will likely last years. Most notably, the $600-per-week increase in unemployment benefits only is in place through July, while expansions in eligibility for jobless benefits and in the number of weeks workers can receive benefits expire at the end of the year. In addition, the boost in SNAP benefits for some SNAP households and the increase in the federal share of state Medicaid costs are both tied to public health emergency declarations so will very likely end before the economy fully recovers.

The measures also have serious gaps. They exclude many immigrants, for example, and provide only modest assistance to those with the lowest incomes; the SNAP benefit boost now in place entirely misses the poorest 40 percent of SNAP households, including at least 5 million children. And the fiscal relief to date for states, localities, territories, and tribes falls far short of projected revenue shortfalls, leaving states and other governments with little choice but to plan for major budget cuts that will, among other harmful impacts, result in layoffs of teachers and other public sector workers as well as workers in businesses and nonprofit agencies that depend on government for business or for funding.

Next Package Should Include Relief That Helps Hard-Hit Households

The next relief package should be robust enough, and last long enough, to ensure that families can make ends meet and are ready to re-engage in the economy fully when it is safe to do so. Relief measures must enable households hit hard by the crisis — whether they lost their jobs directly in the crisis or were already struggling to make ends meet and now face greater challenges — to pay their rent, keep food on the table, and meet other basic needs. Targeting relief to those who most need it is also the most effective way to boost the economy. Moreover, given that the crisis is hitting communities of color and immigrants hardest, funding must be dedicated to programs that have a track record of reaching these communities and have the potential to push back against existing disparities.

Thus, the next package should include two broad sets of measures. The first set should help those struggling the most, by:

- Boosting SNAP benefits for all SNAP participants. The House-passed Heroes Act includes a 15 percent SNAP benefit increase that would provide roughly $100 per month more to a family of four and help all SNAP households, including the poorest households who face the greatest challenges to affording food but were left out of the Families First SNAP benefit increase. Studies show that SNAP benefits are too low even during better economic times; this is particularly problematic during downturns because many participants will be out of work or earning very low pay for longer periods and receive less help from their extended families.

- Significantly increasing funding for homelessness services, eviction prevention, and housing vouchers. Substantial additional resources are needed for rental assistance to enable more struggling households to pay rent, including past missed payments, for as long as they need that help. In addition, the homelessness services system needs more resources to quickly secure housing for people evicted from their homes, revamp its services and facilities in order to facilitate social distancing and other health protocols, and provide safe non-congregate shelter options whenever possible.

- Providing emergency grants to states for targeted help to families falling through the cracks. Even well-designed relief measures will miss some households and do too little for others facing serious crises. The next package should include funding for states to provide cash or other help to individuals and families at risk of eviction or other serious hardships and to create subsidized jobs for those with the greatest difficulty finding employment, when it is safe for employment programs to operate.

- Temporarily expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for workers without minor children at home and the Child Tax Credit for poor and low-income children. Expanding the EITC would help millions of low-wage workers not raising children in their homes who are now taxed into, or deeper into, poverty because they receive either no EITC or a tiny EITC that doesn’t offset their payroll (or in some cases, income) taxes. Providing the full Child Tax Credit to the 27 million children who now receive no or only a partial credit because their families don’t have earnings or their earnings are too low would help children in economically vulnerable families and would be particularly beneficial for children of color.

- Extending important expansions in jobless benefits. The CARES Act temporarily expands the group of workers eligible for jobless benefits (through the new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program), increases unemployment benefit levels, which typically are very low, and increases the number of weeks that workers can receive jobless benefits. These expansions are particularly important for low-paid workers, disproportionately workers of color, who often are ineligible for standard unemployment benefits and receive low benefits when they do qualify. The next package needs to continue both eligibility expansions and benefit improvements and needs to provide access to additional weeks of jobless benefits.

- Providing more help for immigrant families. Immigrant families left out of the stimulus payments should be made eligible for those payments and the package should undo the harmful public charge regulation that is coercing immigrants and their family members to forgo health and nutrition assistance they are eligible for and that could help them weather the economic crisis and access health care during the pandemic.

- Providing relief funding for child care to ensure that providers are available when it is safe to reopen. Like schools, many child care providers shut down in the wake of the pandemic. There is growing concern that without significant relief funding many will go out of business after long closures or periods of sharply reduced enrollment, making it harder for parents to return to work when jobs become available.

The second set of measures should consist of robust fiscal relief for states, localities, tribal nations, and U.S. territories including an increase in the share of Medicaid paid for by the federal government to help meet rising needs for Medicaid and grant-based aid that states and other governments can use to avert deep cuts in education, transportation, and services for struggling households. Even as states’ revenues are plummeting, their costs are rising. More people need help through programs like Medicaid because their earnings are falling or they have lost their jobs and job-based health coverage. Shoring up Medicaid is particularly important for Black and Latino people, who are more likely than white people to get coverage through Medicaid. In addition, public schools and colleges are facing enormous costs to respond to the health crisis, to implement online learning, and (for postsecondary institutions) to cope with reduced tuition revenues.

Without additional aid, states and other governments very likely will cut funding for public services that reduce hardship and increase opportunities, from education to transportation to services for those struggling to get by. That will worsen racial and class inequities that already are growing more acute as a result of the pandemic and recession.[2]

The National Governors Association has called for robust increases in federal Medicaid funding and grant aid to support state and other governments to help address these needs. The House-passed Heroes Act includes robust support in this area.

Boost SNAP to Capitalize on Program’s Effectiveness and Ability to Respond to Need

Failed Reopenings Highlight Urgent Need to Build on Federal Fiscal Support for Households and States

End Notes

[1] Federal surveys generally ask respondents whether they are “of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.” This report uses the term “Latino.”

[2] Nicholas Johnson, “Additional, Well Targeted Fiscal Aid Key to Advancing Racial Equity,” CBPP, July 1, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/additional-well-targeted-federal-fiscal-aid-key-to-advancing-racial-equity. See also Joshuah Marshall, “Tribal Nations Highly Vulnerable to COVID-19, Need More Federal Relief,” CBPP, April 1, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/tribal-nations-highly-vulnerable-to-covid-19-need-more-federal-relief.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work:

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work:

Areas of Expertise

Areas of Expertise