BEYOND THE NUMBERS

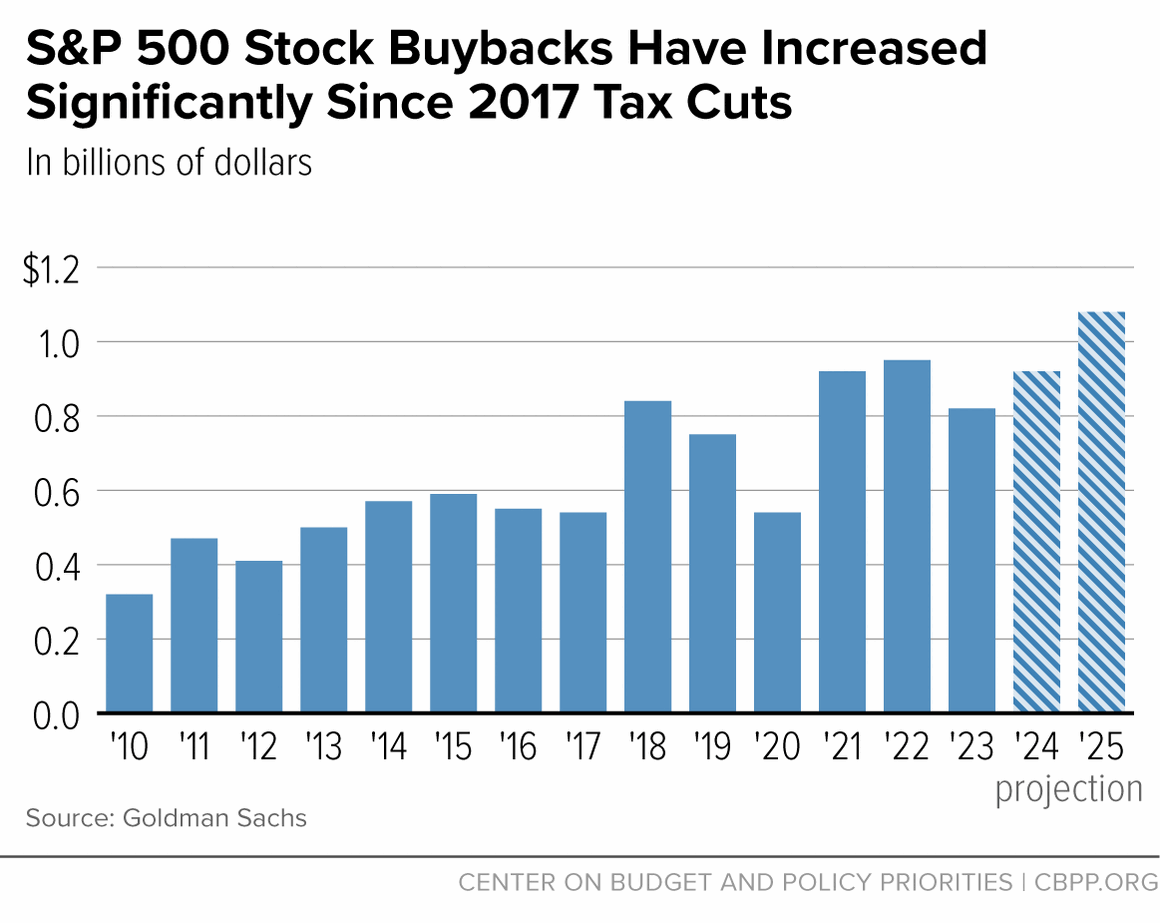

Rather than use their windfalls from the 2017 tax law’s corporate tax cut to increase wages for rank-and-file workers, corporations have boosted stock buybacks, which will exceed $1 trillion in 2025, according to a recent Goldman Sachs analysis. Stock buybacks often raise the value of a company’s stock, increasing the wealth of shareholders. The rise in buybacks is yet another way that the 2017 corporate rate cut translated into higher wealth for the already wealthy, not a mechanism for boosting worker pay.

Other studies have shown that the corporate rate cut overwhelmingly benefits high-income people and has failed to deliver to workers the benefits its proponents promised. The fact that it also launched massive buybacks is a further reason why policymakers should revisit the rate cut next year — part of the larger course correction needed in the nation’s revenue policies as major pieces of the 2017 law expire.

During the 2017 debate, Trump Administration officials said the corporate rate cut, from 35 to 21 percent, would “very conservatively” lead to a $4,000 boost in household income. But a rigorous recent study by economists from the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the Federal Reserve Board found that workers below the 90th percentile of their firm’s income scale — a group whose incomes were below roughly $114,000 in 2016 — saw no change in earnings from the rate cut. Earnings rose only for those at the top, and with the largest gains for those at the very top.

Proponents also promised the rate cut would fuel a surge in investment and economic growth, but meaningful economy-wide impacts have been difficult to find. For example, a new paper from researchers at the Brookings Institution, University of North Carolina, and American Enterprise Institute found that “trends in aggregate investment do not show significant signs of the [2017 tax law].” Also, Jason Furman, former chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, has highlighted that business investment growth was slower in the two years following the law’s enactment than in the two years prior. And the Congressional Research Service noted that investment growth after the law’s enactment was strongest in areas where the law didn’t increase incentives (like intellectual property), which suggests that non-tax factors were at play.

A rate cut of this magnitude — 40 percent — that will cost $1.3 trillion in revenue over the next decade but with limited (and highly uncertain, based on recent research) effects on investment and zero effects on most workers’ wages is a clear policy failure.

While the corporate tax cut hasn’t done much to enhance the well-being of workers, it has fueled a large increase in corporate stock buybacks. This is a process by which a corporation distributes profits to shareholders by offering to buy back a certain number of shares. When this raises the stock’s price, it increases wealth for all stockholders — especially those with the most shares, who are typically wealthier to begin with.

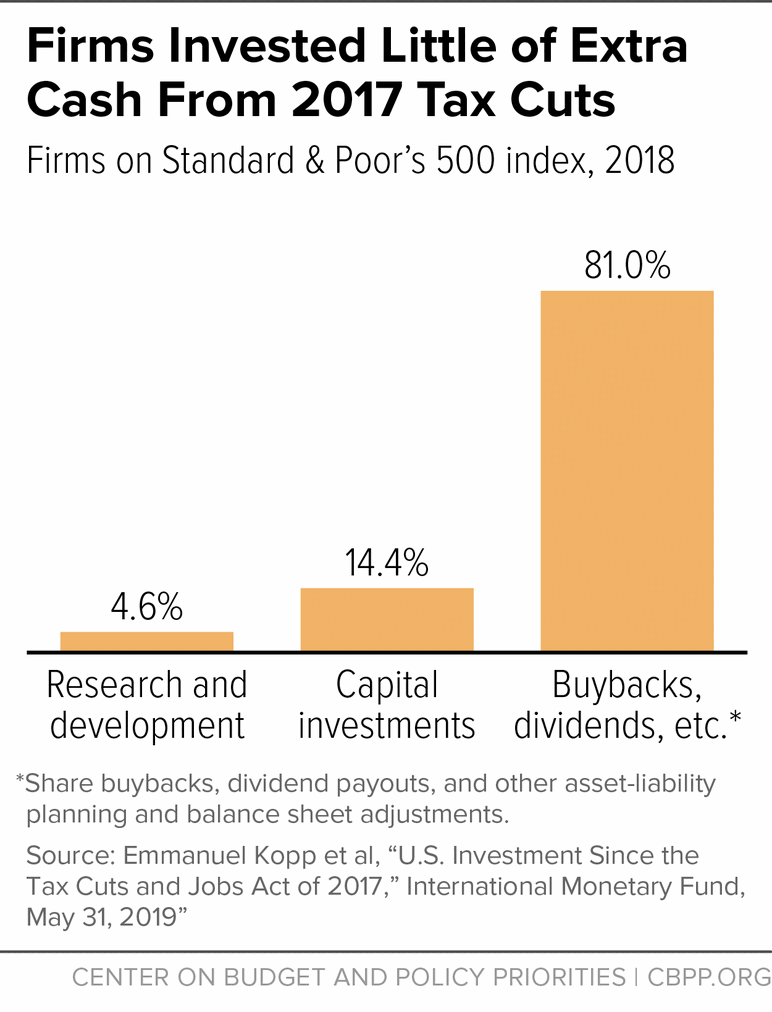

A 2019 International Monetary Fund (IMF) study detailed the rise in share buybacks after the 2017 law, which largely enriched affluent shareholders. Examining data for firms on the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, the IMF researchers asked, “Where then have firms put the incremental free cash from the [tax cuts]?” They found, “only about 20 percent . . . has been used for capital and R&D spending. Much of the remainder was used for share buybacks, dividend payouts, and other asset-liability planning and balance sheet adjustments.” (See first chart.) The paper by JCT and Federal Reserve economists also found that the corporate tax cuts led to an increase in after-tax profits for C corporations, and that “firms returned some of these excess profits to their shareholders” through buybacks and dividends.

The recent Goldman Sachs analysis found that corporations issued record-breaking stock buybacks in 2018, a 55 percent jump over 2017. Excluding the pandemic-induced recession in 2020, buybacks have been markedly higher every year since the 2017 law, and are projected to top $1 trillion in 2025 for the first time. (See second chart.)

These large and growing buybacks bolster the already strong case for raising the corporate rate above 21 percent. The fact that corporations have significant excess cash beyond their investment needs and are using it to further enrich already affluent shareholders suggests that partially reversing the corporate rate cut, as President Biden has proposed, poses little risk to investment or the broader economy. (Policymakers should also raise the excise tax on stock buybacks to 4 percent from the current 1 percent, as we’ll explain in a future post.)

Policymakers have an opportunity to move away from corporate tax cuts that haven’t delivered on their economic promises and toward a tax system that raises more revenue through progressive policies like increasing the corporate tax rate. They can then use those revenues for investments to make the economy work better for everyone, such as an expanded Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit, child care, and housing.