As Washington turns its attention from providing short-term relief to millions of struggling people through the American Rescue Plan Act to building an equitable recovery for the long term, policymakers have an historic opportunity to rebuild the nation’s infrastructure and to begin addressing its long-standing economic and racial disparities that COVID-19 and the economic fall-out both highlighted and exacerbated. Policymakers will likely seek to finance recovery legislation through federal borrowing as well as tax increases on wealthy individuals and profitable corporations.

In outlining his vision for the first of a two-part recovery package, President Biden proposed roughly $2 trillion of infrastructure, research and development, and other investments, financed over 15 years by raising the corporate income tax rate from its current 21 percent to 28 percent and reforming our international tax system to raise revenue and reduce incentives for U.S. multinational corporations to shift profits and investments overseas.[1] These changes would leave the corporate rate still significantly below its previous level of 35 percent, which President Trump and a Republican-run Congress cut to 21 percent in the 2017 tax law. And the revenues these permanent changes would raise would begin to restore the nation’s eroded revenue base so that it can support the needs of a 21st century economy that broadens opportunity, supports workers and those out of work, and ensures health care for everyone.

When evaluating President Biden’s corporate tax proposals, we suggest that policymakers keep four points in mind:

- First, raising taxes on corporations would make the tax code more progressive while helping to generate the revenue needed to help finance investments that would promote an equitable recovery;

- Second, the dramatic corporate tax cuts of 2017 provided few benefits to the economy in general and to low- and middle-income households in particular;

- Third, raising corporate taxes by a modest amount will not undermine the economic recovery and, in fact, using those revenues to finance needed investments will help make the economy stronger; and

- Fourth, reducing the favorable tax treatment for offshore profits and investments, which the 2017 law largely did not do, would ensure that U.S. multinationals pay their fair share while positioning the United States as a leader in global tax negotiations.

Corporations, including multinationals, that operate in the United States derive considerable benefit from the federal government. These companies rely heavily on our roads, airports, and ports to move their goods and employees. But they also benefit greatly from the government’s role in the research and technology development process, with huge contributions by, for instance, the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. Private companies benefit from the large spillover effects of this government-funded research, and they also benefit from public investments in education, public health, and a clean environment — and a host of other areas that help workers, communities, and companies thrive. Asking profitable corporations that gain so much from public investments to pay more to fund them is one important way to build toward a more equitable nation.

Incomes and wealth have grown more highly concentrated at the top in recent decades and, over the last two decades in particular, tax policy helped to fuel this growing divide between the wealthiest households and all the rest.

Most prominently, the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts under President George W. Bush cut individual tax rates and reduced the tax on estates, both of which provided the largest tax benefits to the highest-income taxpayers. The 2017 tax cuts under President Trump dramatically cut the corporate tax rate, cut the top individual income tax rate, further weakened the estate tax, and created a big new tax deduction on “pass-through” business income (business income from partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships). A disproportionate share of these tax benefits flowed not only to corporations but, once again, to households at the top.

All of that tax cutting also significantly reduced federal revenues. Federal revenues as a share of the economy (gross domestic product, or GDP) stood at 20 percent in 2000. In 2019, at a similar peak in the business cycle, federal revenues had fallen to just 16.3 percent of GDP — which is far too low to support the kinds of investments needed for a 21st century economy that broadens opportunity, supports workers and helps those out of work, and ensures health care for everyone.

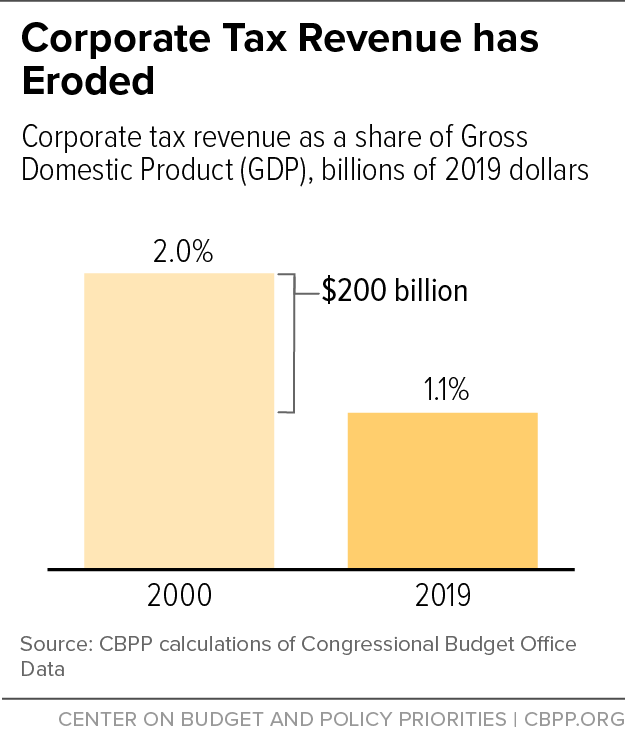

As part of that overall reduction in federal revenues, the corporate income tax’s contribution to revenues fell by roughly half, from 2.0 percent of GDP in 2000 to about 1.1 percent in 2019. That alone amounts to roughly a $200 billion annual loss of revenue. (See Figure 1.) The Biden proposal reportedly would lift annual revenues by about 0.5 percent of GDP, recapturing about half of this revenue erosion.[2] As a share of GDP, the U.S. federal government receives less revenue from the corporate tax than that of all but one other country of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (or OECD, an organization of 37 mostly Western nations with mostly advanced economies).[3] Meanwhile, corporate profits of U.S. companies as a share of GDP are quite high: according to Deputy Assistant Treasury Secretary Kimberly Clausing, “corporate profits (after-tax) as a share of GDP averaged 9.7 percent (2005-2019), whereas in the period 1980-2000, corporate profits averaged only 5.4 percent of GDP.”[4]

President Biden’s proposal to raise the corporate tax rate to 28 percent, reversing only part of the 2017 rate cut, would help make the tax code more progressive and help generate the revenues to finance needed investments. The burden of a corporate rate hike would fall mostly on corporate shareholders, who reaped most of the benefit of the 2017 corporate tax cut. “Shareholders, in the short run and, mostly, in the long run, bear the burden of higher corporate tax rates,” according to the Tax Policy Center’s Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke.[5] Wealthy shareholders have enjoyed significant wealth gains even during the pandemic that left many out of work and households struggling to afford food.

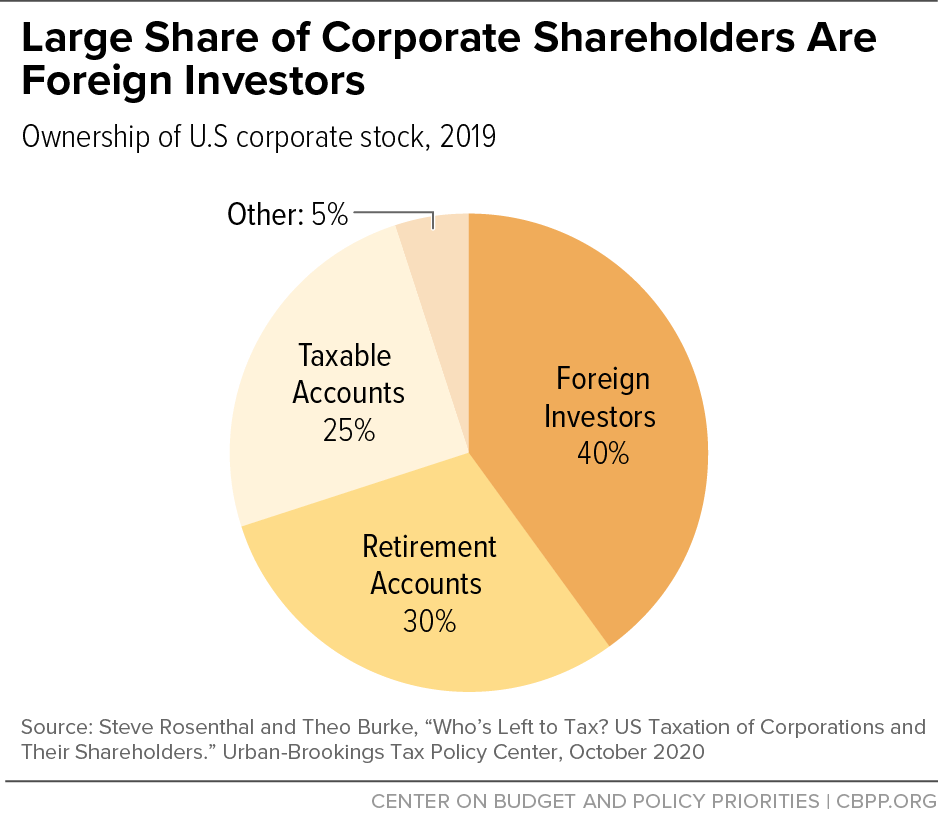

The ownership of corporate shares — as with other kinds of wealth — is highly concentrated at the top. Foreign investors own about 40 percent of U.S. corporate equity (up from just 11 percent in 1980), while retirement accounts own about 30 percent, and investors with taxable accounts own about 25 percent. (See Figure 2.) Within the latter two categories, wealthy households directly or indirectly own the vast majority of corporate stock: “The top 10 percent of households, on average, own $1.7 million of stock, directly and indirectly,” Rosenthal and Burke concluded, “while the bottom 50 percent only own about $11,000.”[6]

Stock ownership is also increasingly concentrated among the ultra-wealthy. “The wealthiest 0.1% and 1% of households now own about 17% and 50% of total household equities, respectively, up significantly from 13% and 39% in the late 1980’s,” according to Goldman Sachs senior economist Daan Struyven.[7]

Nor, despite the claims of those who oppose corporate tax increases, would low- and middle-income workers bear much of the burden of a corporate tax increase. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), and the Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis all agree that only a quarter or less of the burden of corporate taxes falls collectively on workers. And, of that one-quarter or less, the burden would fall mostly on upper-income workers (that is, far more on a CEO more than a blue-collar worker) simply because, by definition, upper-income workers have more labor income that would feel the modest side effect of the corporate income tax.

Moreover, workeprs and their families would benefit significantly from the investments that a corporate tax increase would help finance.

The centerpiece of the 2017 law was a corporate tax rate cut from 35 to 21 percent[8] and a shift towards a “territorial” tax system, in which the foreign profits of U.S.-based multinational corporations largely no longer face U.S. corporate taxes. For budgetary reasons, policymakers could not make all of the 2017 law’s tax cuts permanent. They made the corporate tax cuts permanent while scheduling every tax cut for individuals (e.g., an increase in the Child Tax Credit) to expire after 2025.

Efforts to reform corporate taxes by broadening the base of corporate profits that’s subject to taxation and lowering the rate were widely debated before 2017, but few serious plans proposed to cut corporate taxes as drastically as the 2017 law did.

President Obama, for example, proposed cutting the corporate rate to 28 percent[9] but, in contrast with the 2017 law, his plan would not have generated higher deficits because it would have broadened the corporate and business tax base. Before the 2017 law, the main Republican corporate tax reform proposal was the 2014 plan from then-House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp,[10] which would have cut the corporate tax rate to 25 percent. Importantly, the Camp plan would have moved away from aggressive accelerated depreciation, which lets businesses claim larger upfront deductions for new investments, as part of an effort to broaden the tax base while reducing the rate. The 2017 tax law, however, went in the opposite direction of Camp’s proposal on depreciation (providing full expensing, which lets businesses deduct the full cost of investments immediately) and cut the corporate rate even more deeply than the Camp plan.

Though the corporate rate cut of 2017 was dramatic (by two-fifths — from 35 to 21 percent), the large economic benefits that its proponents promised have been hard to find. In February of 2020, Jason Furman, the Chairman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, told the Ways and Means Committee that:

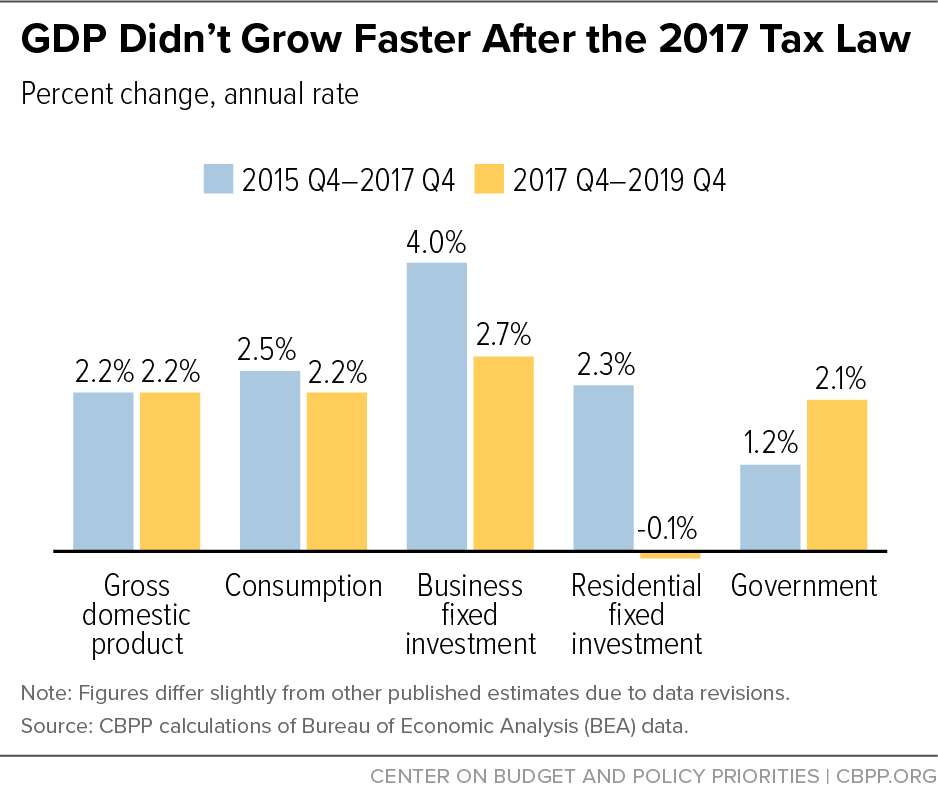

- “GDP growth did not increase following the 2017 tax law: it was 2.4 percent in the eight quarters leading up to the law and 2.4 percent in the eight quarters since the law;

- “The major private domestic components of GDP slowed in the two years since the 2017 tax law, including slowing consumption growth, business fixed investment growth and residential investment growth. In contrast, government expenditures and investments grew at a faster pace; (see Figure 3) and

- “The macroeconomic data to date appear to rule out the immediate and large effects on investment that were predicted by many cheerleaders of the 2017 tax law and provide no reason to update the ex ante projections of minimal longer-term growth effects made by a range of economic modelers.”[11]

Similarly, in a Congressional Research Service report of June 2019, Jane Gravelle and Donald Marples highlighted that:

- Workers did not see the increase in wages that proponents of corporate tax cuts promised: “There is no indication of a surge in wages in 2018 either compared to history or to GDP growth.” They also noted that gains in worker wages depend on increases in investment that ultimately raise productivity, but the investment data do not reveal investment increases either.[12]

- Disproportionate increases in the types of investment that the 2017 law sought to encourage have not materialized, further undercutting the view that the tax cuts are driving an investment surge. Based on the law, for example, they note that the “effects of investments in structures would be expected to be largest, with small (or negative) effects on intellectual property. To date this pattern has not been observed.”

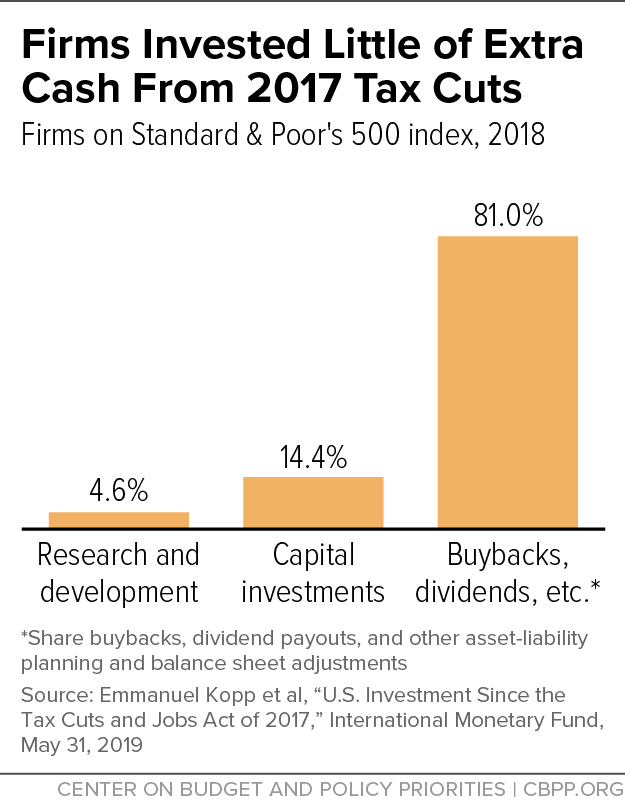

Well-publicized, one-time bonuses for employees that companies announced after the tax cuts were modest overall — averaging $28 per U.S. worker, and amounting to just 2 to 3 percent of the total benefits from the corporate tax cut — while announcements of stock buybacks, which benefit shareholders by raising the value of the stock they already hold, exceeded a record-breaking $1 trillion in 2018.

An International Monetary Fund (IMF) study on the 2017 law’s impact on investment further detailed this pattern of share buybacks.[13] It cited a survey of firms showing that just 11 percent of businesses reported accelerating investment because of the tax cuts. Examining data for firms on the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, the IMF researchers asked, “Where then have firms put the incremental free cash from the [tax cuts]?” and answered that “much of the remainder was used for share buybacks, dividend payouts, and other asset-liability planning and balance sheet adjustments.” (See Figure 4.)

Every major tax debate of recent decades has included overheated claims that tax increases will cause economic doom or that regressive tax cuts will generate enormous economic benefits. The latest installment of that debate, in fact, has already begun, with some policymakers now arguing that the President and Congress should not raise taxes as the economy continues to recover from the recession.[14] There are, however, several key points to keep in mind about the recovery and corporate taxes.

First, with no evidence that previous corporate tax cuts significantly boosted investment and economic growth, there is no reason to believe that partially undoing those cuts would significantly slow investment and growth. Slashing the corporate tax rate in 2017 largely enriched well-off shareholders, not the broader economy, and the impact of partially reversing these tax cuts would be borne mainly by these shareholders.

Second, there is little evidence that a corporate rate hike would hinder wage growth, which is a key measure of whether the burgeoning recovery becomes a successful one, particularly for lower- and middle-income workers. Indeed, as a report from the Economic Policy Institute put it, “Since World War II, productivity and wage growth in the U.S. economy have been significantly greater in periods with higher corporate tax rates.” [15] That doesn’t mean that higher corporate tax rates caused the wage growth, but it is strong evidence that the tax rates didn’t unduly impede wage growth either.[16]

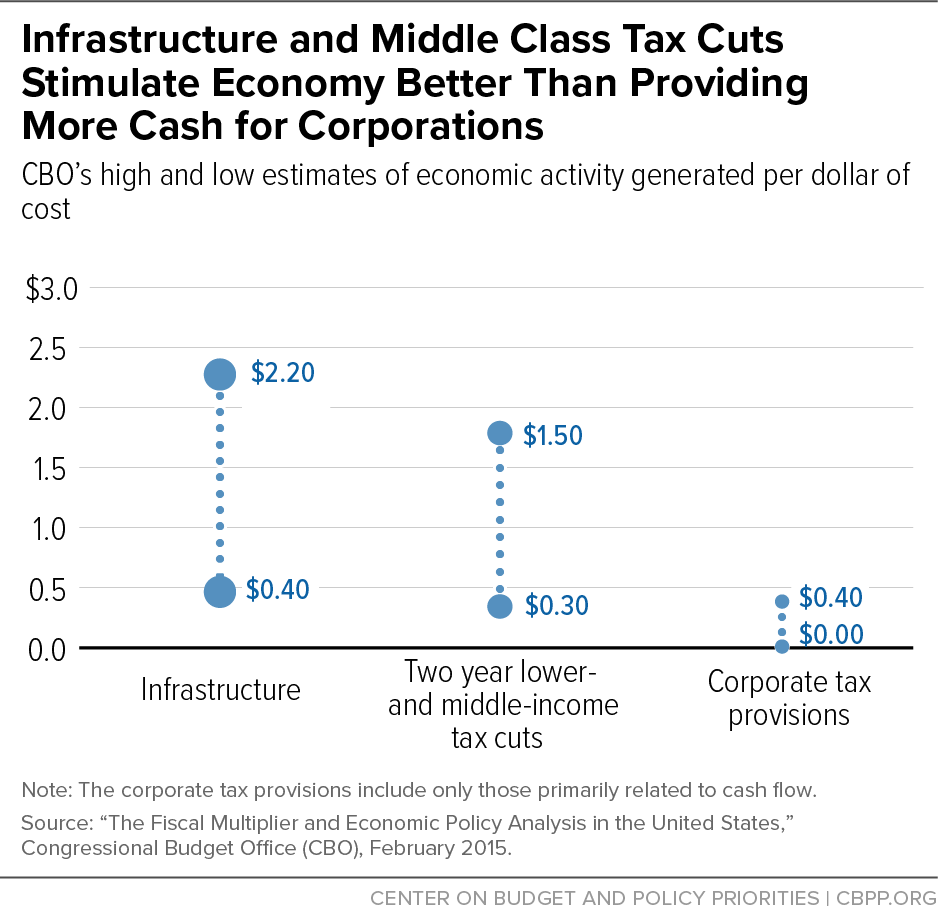

Third, an important consideration is what policymakers would do with the revenue they raise by boosting the corporate tax rate. Of the Biden proposal, Harvard economist Raj Chetty told the Washington Post, “The impacts of the infrastructure programs are likely to be an order of magnitude larger than any disincentive effects from the taxes.”[17] Per Figure 5 below, CBO found that infrastructure investment or tax cuts for low- and moderate-income households will boost an economy that is still emerging from a deep recession more than a corporate tax cut. So, raising corporate taxes and investing the funds in infrastructure or an expanded Child Tax Credit would, on net, boost the recovery.

A new analysis by Mark Zandi and Bernard Yaros of Moody’s Analytics, using a model similar to those used by the Congressional Budget Office and Federal Reserve Board, estimated the combined impact of the American Jobs Plan’s infrastructure investments and corporate tax increases.[18] It found that:

- “Despite the higher corporate taxes and the larger government deficits, the plan provides a meaningful boost to the nation’s long-term economic growth,” with “higher GDP, more jobs and lower unemployment.”

- The plan would produce an estimated 2.7 million jobs, most of which would go to people with lower income.

These net positive economic effects reflect the large returns from the plan’s infrastructure investments and the modest impacts of partially undoing the 2017 corporate tax cuts. “Long term, economic research is in strong agreement that public infrastructure provides a significantly positive contribution to GDP and employment,” the report explained. Yet combined federal, state, and local infrastructure investment has fallen for more than half a century, according to the report, from around 6 percent of GDP in the 1950s and 1960s to less than 1 percent today.

And fourth, specifically with regard to the recovery from COVID-19 and its economic fall-out, another important consideration is the deep economic and racial disparities that this crisis both highlighted and exacerbated. While millions of lower-income families and individuals continue to face financial hardship due to COVID-19 and the economic fall-out, those at the top in large measure continued to prosper during these hard times — a dichotomy that has become known as the “K-shaped” recovery.[19] Raising taxes on those struggling during this crisis could create headwinds for the recovery, but a corporate tax hike would predominantly fall on those wealthier people who have already recovered from (or never experienced) the recession. A robust and equitable recovery requires that policymakers prioritize still-struggling households, and that’s precisely what raising corporate revenue to fund public investments will do.

Before the 2017 tax law, multinational corporations could shield large amounts of their profits from taxation by shifting profits and operations overseas to low-tax countries (known as “tax havens”). The 2017 tax law made a series of changes to the international tax regime, but it ultimately left in place (or created new) large incentives to shift profits on “paper” as well as actual investments and operations overseas.[20] That law, for example, permanently excludes from tax certain income of U.S. multinationals and it taxes other foreign profits at a low 10.5 percent rate (or half the domestic corporate tax rate). Two years after the law’s enactment, the amount of profit shifting by U.S. multinationals is virtually identical to that before the law.[21]

President Biden’s plan seeks to better limit federal tax incentives for companies to shift their profits and investments overseas to where they face little or no tax. It seeks, for instance, to strengthen the current minimum tax on certain foreign profits to ensure that more of the foreign income of U.S. multinationals faces the tax, and that it’s taxed at a higher rate. To encourage other countries to enact similar minimum taxes, the plan would deny certain deductions to non-U.S. multinationals with U.S. operations if they are headquartered in countries that don’t impose minimum taxes. Other countries should adopt minimum tax measures as well in order to ensure that companies’ decisions on where to locate and where to “book” their profits are not based on differences in countries’ corporate tax systems.

The United States can do a lot, on its own and in coordination with other countries, to discourage the corporate tax “race to the bottom,”[22] which refers to countries cutting their corporate taxes to encourage multinationals to locate within their borders. As Deputy Assistant Treasury Secretary Clausing put it, “the present moment is an ideal time to reform our international tax rules, since there is a strong international consensus around addressing these problems, and our action can encourage action abroad.”[23]

Reforming U.S. taxes on the foreign profits of U.S. multinationals would position the United States as a global leader in international taxation, which is especially important this year as OECD countries work toward a once-in-a-century global tax deal. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has expressed a desire to engage “robustly”[24] in these negotiations, and Congress should support that effort.

Moreover, reforming the international tax system would raise significant revenue to invest in infrastructure and workers, which is a far better way to strengthen the economy and support innovation than continuing to permit large-scale tax avoidance by multinationals that drain U.S. revenues and encourage multinationals to locate profits and investment offshore.